OK, just when you thought it was safe to forget about the overindulgence and caloric excesses of Thanksgiving day, here comes another blog post on Thanksgiving recipes. This one sticks to the basics: roasting the turkey itself and making gravy. It is my traditional holiday task to make the dim-witted bird into a delectable feast (and yes, I know wild turkeys are very smart), so this recipe has matured with age–unlike me. So grab your blunderbuss, put on your Pilgrims hat, and let’s get to it.

OK, just when you thought it was safe to forget about the overindulgence and caloric excesses of Thanksgiving day, here comes another blog post on Thanksgiving recipes. This one sticks to the basics: roasting the turkey itself and making gravy. It is my traditional holiday task to make the dim-witted bird into a delectable feast (and yes, I know wild turkeys are very smart), so this recipe has matured with age–unlike me. So grab your blunderbuss, put on your Pilgrims hat, and let’s get to it.

First a few basic points.:

- The Bird–I have a preference for fresh-killed turkeys over frozen–their water and fat content is lower (avoid pre-basted turkeys at all costs: the all-too-common Butterball is an abomination, if you must know, literally dripping with hydrogenated vegetable oil, the worst kind of fat). I have had a so-called “free range” turkey one year: excellent taste, but they are pricey, a bit dry, and relatively hard to get in my neck of the woods. We tend to have a lot of folks for dinner on holidays, so we usually get big birds–25 pounds this year.

- The Pan–a large, heavy roasting pan is a necessity; the disposable foil ones are not only flimsy, but they seem to prevent browning to considerable degree, and definitely prevent the caramelization of the pan drippings and ingredients essential to making a good gravy.

- The Rack–a good sturdy adjustable roasting rack is also a must. Letting the turkey sit on the bottom of the pan causes it to stew, prevents proper cooking and reduction of the pan drippings, and generally leads to a sodden mess unfit for eating.

- The Oven–I have the good fortune to have a convection oven in my home, which is superb for roasting, as it cooks more quickly and at lower temperatures. The gas-or-electric dispute approaches a religious war in some circles; electric is easier to regulate temperature-wise in my mind–and besides, that’s what I have. Oh, and no foil tents–tin foil is ideal for conspiratorial hats and the like, but terrible for roasting, stewing the meat instead of roasting it.

- The Temperature–I like keeping the temperature relatively low–the bird cooks more slowly, and browns more evenly. I use 325 degrees throughout; without convection, I’d move up to 350. Rack low in the oven.

- The Saucepans–you’ll need two heavy sauce pans, one 4 quart (for the stock), one at least 2 quart (for the gravy). Of the two, the gravy pan is the most important, as even heat distribution with no hot spots is important when making the roux.

- The Ingredients–if you’re looking for exact quantities here, you’re outta luck: this is definitely an eyeball project. Use fresh ingredients and spices–I am partial to Penzey’s spices, which are outrageously fresh and aromatic, compared to the decades-old spice bottles on the shelf at your local supermarket.

The project begins with the roasting pan–you must be thinking of the end when at the beginning. The key to a superb turkey gravy (or any meat gravy, for that matter) is in the pan drippings. The sugars caramelize to a dark brown, providing exquisite flavor and rich color critical for good-tasting gravy.

I place the roasting rack in the pan, and surround it with sweet onions (Walla Wallas, Vadellias, or Mexican) coarsely chopped, chopped celery, a hefty handful of whole peppercorns (Penzeys has a 4-pepper blend which is both colorful and relatively mild), and yes–your eyes aren’t lying–apple slices. I use a crisp, moderately sweet apple (Fujis here in the Northwest). During roasting, the apples disintegrate, adding both sugars for caramelization and lots of liquid for the gravy stock.

Next comes the turkey stock, which will be used in addition to the pan drippings for the gravy. In the 4 quart stock pan, I place the giblets, the gizzard, and the neck, followed by celery and celery leaves (the leaves have much more flavor than the stalks), a large chopped onion, several cloves of garlic, some celery seed, a pinch of salt, and more peppercorns. Fill the pan about 4/5 with water, and simmer slowly on a back burner while preparing and cooking the bird.

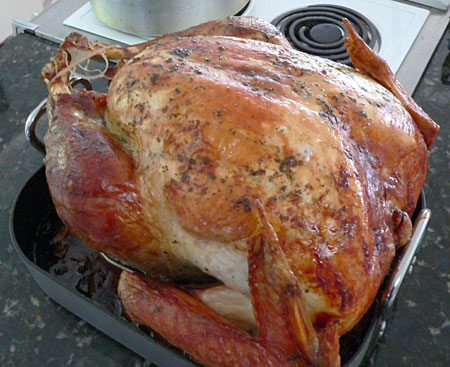

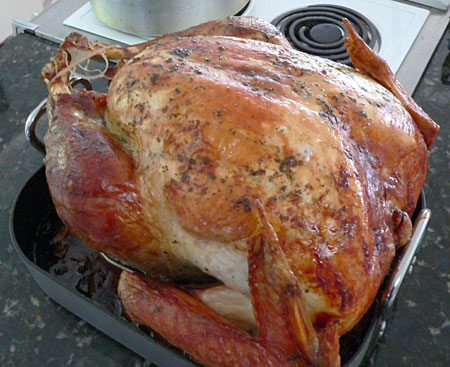

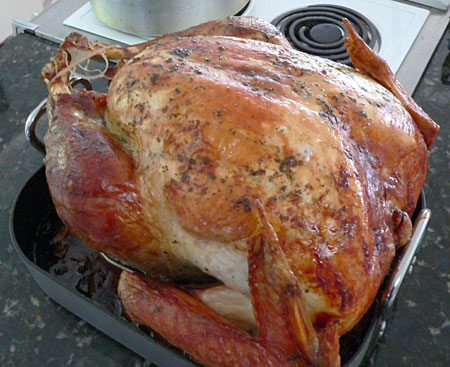

Now on to the bird: I pat the skin dry (moisture prevents browning), place the bird breast-side down on the rack, and place lots of butter and a hefty sprinkling of pepper and tarragon. (If you’re on a low-fat diet, this is not the meal for you; for the rest of us, that’s why God created Lipitor). The breast-down approach keeps the breast moist as it cooks. As you may notice, this turkey is ridiculously large for the pan–kinda like an elephant wearing a miniskirt. It works–but just barely (a larger roaster is on Santa’s list for this year, so I’m being nice not naughty). The bird then goes in the oven.

I baste it periodically with a butter-tarragon mixture, kept over the oven vent to keep just melted without burning.

Cooking time? Anyone’s guess–it depends on the oven, the size of the bird, convection vs. non-convection. I generally give a bird this size about 1-1 1/2 hours breast down, basting every half hour and watching for the golden brown color of the skin.

Now it’s time to flip the bird (I practice in the off-season while driving on the freeway). One heavy carving fork goes in the neck cavity, another in the tail, and a helping hand holds the rack down during the process.

As you can see, the breast is very moist, and has not browned at all. It is basted with the butter-tarragon mixture, and popped back in the oven. Notice the red dot: this is a cooking indicator. When the meat reaches temperature, a restraining wax melts, allowing a red thingy to pop up. Problem is, it’s hardly foolproof: I’ve had them stick, resulting in a desiccated bird–if you like pterodactyl, it’s just the thing. Your eyes, nose, and fingers are better judges of when it’s done. This bird took about 3 hours 20 minutes.

Turkey, like most fowl, is a bit tricky to roast, as the dark meat on the bones cooks at a different rate from the breast meat. I lean toward white meat that’s still pretty moist (but not pink), which generally leaves the thighs done about right. The indicators I use are the skin color; juices which run clear from the thigh; and a firm breast meat texture to compression. Wish I could be more specific, it’s an experience thing: if you’re uncertain, use a meat thermometer. I rarely do any longer.

Once it’s done, I turn my attention to the gravy. The turkey is removed from the rack, and the rack scraped to get all its precious drippings into the roasting pan. I then add some of the clear turkey stock we made above to the pan, and heat it on the stovetop while gathering all the caramelized drippings into solution.

Notice how the apples and the onions have largely disappeared.

The drippings are then poured out of the pan into a large measuring cup, using a sieve or a press to squeeze the juice out of the solids. The fat (butter plus turkey fat) rises to the top–some of this will be used for the roux, to thicken the gravy, the rest discarded. Notice that the quantity of fat is relatively low–with a Butterball, you will have 4-5 times this amount, and it’s nasty and high in salt.

Some of the fat is then skimmed and added to your gravy pan–the amount depends on how much gravy you want, though I tend to be generous. Heat the fat over medium-low heat, until the water-based drippings just start to simmer.

The key to smooth, unlumpy gravy is the roux and the liquid addition. A roux is a flour-fat mixture– most commonly butter and flour–which is cooked together before adding liquid. The cooking creates a paste which eliminates the raw flour taste, and which will absorb a lot of liquid.

I add enough flour to make a paste about the consistency of cookie dough, and cook it slowly, avoiding burning or browning, for about 5-10 minutes. I then gather the roux on one side of the pan, leaving the heat about the same.

The dark liquid from the drippings (sans fat) is then added using a ladle, a little at a time, allowing it to heat up to a simmer in the bare pan before stirring. To avoid lumps, the roux must be well-cooked and blended, and the liquid hot, and added in small amounts initially. As you begin to blend the drippings into the roux, it will actually thicken at first, becoming quite stiff.

Repeating the routine–pushing aside the roux, adding liquid until hot, then thoroughly blending before adding more liquid–you will get to a stage where the paste is smooth and the consistency of thick pudding. At this stage, you may begin to add a little more liquid at a time.

The liquid from the pan drippings gives the gravy a rich, brown color–almost too dark. At this stage, I strain the clear turkey stock created earlier, and begin adding it to lighten the color and add more flavor. I tend to end up with a relatively thin gravy, which will thicken as it stands and cools.

The final touch is seasoning: salt and pepper. Taste it first–I use a lot of peppercorns, so more pepper is rarely needed, but salt sometimes is necessary.

So there you have it–all ready for feasting and piling on a few more pounds to take off after New Years.

It was, at the outset, about direction. Direction demands trust.

It was, at the outset, about direction. Direction demands trust.

OK, just when you thought it was safe to forget about the overindulgence and caloric excesses of Thanksgiving day, here comes another blog post on Thanksgiving recipes. This one sticks to the basics: roasting the turkey itself and making gravy. It is my traditional holiday task to make the dim-witted bird into a delectable feast (and yes, I know wild turkeys are very smart), so this recipe has matured with age–unlike me. So grab your blunderbuss, put on your Pilgrims hat, and let’s get to it.

OK, just when you thought it was safe to forget about the overindulgence and caloric excesses of Thanksgiving day, here comes another blog post on Thanksgiving recipes. This one sticks to the basics: roasting the turkey itself and making gravy. It is my traditional holiday task to make the dim-witted bird into a delectable feast (and yes, I know wild turkeys are very smart), so this recipe has matured with age–unlike me. So grab your blunderbuss, put on your Pilgrims hat, and let’s get to it.

A wise friend–a man who helped me emerge from a period of considerable difficulty in my life–once taught me a simple lesson. In less than a minute, he handed me a gift which I have spent years only beginning to understand, integrating it into my life with agonizing slowness. It is a lesson which intellect cannot grasp or resolve, which faith only begins to illuminate–a simple principle which I believe lies close to the root of the human condition.

A wise friend–a man who helped me emerge from a period of considerable difficulty in my life–once taught me a simple lesson. In less than a minute, he handed me a gift which I have spent years only beginning to understand, integrating it into my life with agonizing slowness. It is a lesson which intellect cannot grasp or resolve, which faith only begins to illuminate–a simple principle which I believe lies close to the root of the human condition.

Damn!, I hate these calls…

Lying on my desk, clipped to a yellow manila binder, is a single sheet of paper. Its pleasant color format and sampled photomicrograph belie the gravity of its content:

Damn!, I hate these calls…

Lying on my desk, clipped to a yellow manila binder, is a single sheet of paper. Its pleasant color format and sampled photomicrograph belie the gravity of its content:

Several months ago, I upgraded my voice recognition software to Dragon NaturallySpeaking version 8. I have been using voice recognition software for over five years now, and have been very satisfied with it, although older versions could be maddening at times–and hilarious at others. This version is amazingly accurate–my only complaint since upgrading is that I am not having nearly as much fun proofreading my notes as I have the past.

Several months ago, I upgraded my voice recognition software to Dragon NaturallySpeaking version 8. I have been using voice recognition software for over five years now, and have been very satisfied with it, although older versions could be maddening at times–and hilarious at others. This version is amazingly accurate–my only complaint since upgrading is that I am not having nearly as much fun proofreading my notes as I have the past.  They say that hell is hot. Sometimes, though, it is very, very cold.

They say that hell is hot. Sometimes, though, it is very, very cold.