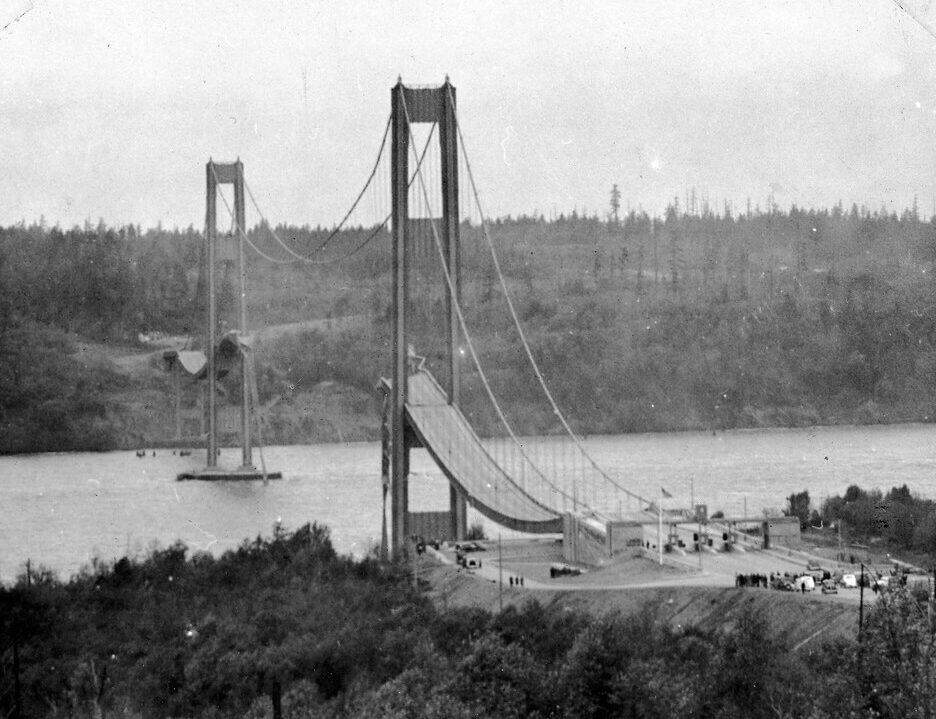

I am fortunate to live near an engineering marvel recently completed: the new Tacoma Narrows bridge. Most folks have heard of the Tacoma Narrows bridge — at least the first one, “Galloping Gertie”, which catastrophically failed during a windstorm in November 1940.

Built at the cost of $6.6 million dollars, designed by world-famous bridge architect Leon S. Moisseiff (who also designed the Golden Gate bridge), it embraced the light, elegant design principles in vogue at the time – and was designed with complete ignorance of the aerodynamic effects of high winds on bridges. Moisseiff had inadvertently created a mile-wide airplane wing, with its light-weight narrow deck and plate-girder sides. It survived only 4 months after completion. In a strong-but-typical November windstorm, the wave-like undulations were severe enough to unseat a cable from its saddle on the West tower, creating a corkscrew torsional motion which ripped the bridge to shreds.

The only casualty, surprisingly, was Tubby the three-legged dog.

May he rest in peace.

Designed to carry 60,000 cars per day, the second bridge ferries over 90,000, and had become a major choke point for traffic in the rapidly growing South Puget Sound area. These transportation pressures have given rise to the new Tacoma Narrows Bridge project.

The Tacoma Narrows is a formidable natural barrier. Carved out by ancient glaciers, over a mile wide and 260 feet deep, with steep, unstable banks on either side, it is a hostile environment for a suspension bridge. Wild tidal currents rip through the Narrows twice daily, through the sole portal between the Pacific Ocean and the entire South Puget Sound. High winds and fog are common. The Puget Sound area is also prone to major earthquakes.

The new Narrows Bridge project was the largest engineering endeavor in the U.S. in the last 30 years. Construction began in late 2002, after approval of an $800 million public-private financing package. On the east and west banks are the anchors — enormous concrete fortresses designed to secure the cables with their huge tractive forces to the sandy glacial till on either side of the Narrows.

After the caissons have been seated on the floor of the Narrows, the towers begin their rise from the caissons.

More on these on subsequent posts.