The ethics of euthanasia, which as an issue generally stays just barely on our radar screens, given the host of contentious social issues taking up our political and cultural bandwidth, nevertheless may ultimately prove to be an enormous dilemma, with profound impact on both our lives as a society and as individuals. While the issue has only occasionally nosed into the political limelight–usually associated with some initiative regarding physician-assisted suicide–the underlying currents which keep this matter very much alive are powerful and unlikely to be resolved easily or painlessly.

There is broad appeal for the idea of euthanasia. It seems to fit perfectly into our Western democratic principles of the autonomy of the individual, rights and freedom, and the desire to control our own destinies. It seems as well an ideal solution to an out-of-control health care system, where technology and advances in life-sustaining capabilities seem to have taken on a life of their own, driving health care costs to extraordinary levels in the final years of our life, and seemingly removing much of the dignity we believe should be the inherent right of the dying. Patient’s families watch helplessly as their loved ones appear to be strung along in their dying days, tubes and wires exiting from every orifice, a relentless train of unknown physicians and ever-changing nurses breezing in and out of their rooms to tweak this medication or that machine. We all wish for something different for ourselves as well as our loved ones, but seem to be incapable of bringing that vision to fruition.

Euthanasia offers what appears to be an ideal solution to many of these difficulties. We love the idea that the individual may choose the time and place of their own demise; we see an easy and painless exit to prolonged suffering; we visualize a measure of mastery returning to a situation where are all seems out of control; we see a solution to pointless expenditures of vast sums of money on patients with little or no hope of recovery. It is for these reasons that initiatives to legalize this process are commonly called “death with dignity” or some similar euphemism reflecting these positive aspects–and when put forward, often find as a result a substantial degree of public approval.

This appeal grows ever stronger as our culture increasingly emphasizes personal autonomy and de-emphasizes social responsibility. We are, after all, the captains of our own ship, are we not? A culture which believes that individual behavior should be virtually without limit as long as “no one is harmed” can see little or no rational reason why such individual autonomy should not be extended to end-of-life decisions.

The reality, unfortunately, is that “no one is harmed” is a uniquely inadequate standard for human behavior, and our autonomy is far less than we would like to believe. It assumes that human behavior occurs in a vacuum. Thus we hear that sexual relations between consenting adults are entirely reasonable if “no one is harmed”–a standard commonly applied to relationships outside of marriage, for example, which often end up having a profound and destructive effect both on the spouse–and particularly on the children. “No one is harmed” serves as mere justification for autonomous behavior while denying or minimizing the inevitable adverse consequences of this behavior. When Joe has an affair with Susie at the office, and ends up in divorce court as a result, there can be little question that many are harmed: Joe’s children, not the least; his wife; perhaps the husband and children of the woman with whom he has had an affair. Yet in the heat of passion, “no one is harmed” is self-evident–believed even if false. And to mention these obvious ramifications of a supposedly “harmless” behavior is to be “judgmental” and therefore must be assiduously avoided.

But the consequences are real, and their ripple effect throughout society is profound: to cite one simple example, children from broken homes are far more prone to become involved in gangs or crime, to be abused sexually or physically; to initiate early sexual activity and become unwed mothers; to under-perform academically, and to have greater difficulty with relationships as teenagers and adults. These effects–particularly when magnified on a society-wide scale–have effects vastly broader than the personal lives of those who have made such autonomous choices.

Similarly, an argument is often used by libertarians (and others) for drug legalization using this same hold-harmless rationale. After all, who could argue with personal drug use in the privacy of your home, since “no one is harmed?” No one is harmed, of course–unless the residual, unrecognized effects of your drug use affects your reflexes while driving the next day, resulting in an accident; or impairs your judgment at work, costing your employer money or resulting in a workplace injury; or when, in the psychotic paranoia of PCP use, you decide your neighbor is trying to kill you, and beat him senseless with a baseball bat; or when the drug itself, in those so physiologically prone, leads to addictive behavior which proves destructive not merely to the individual, but to family, fellow workers, and society as a whole. Burning up every spare dollar of a family’s finances to support a drug habit, and stealing to support it–surely not an unusual scenario–can hardly be qualified as “no one is harmed.” To claim that there is no societal impact from such individual autonomous behavior is profoundly naive, and represents nothing more than wishful thinking.

But what about euthanasia? Surely it is reasonable to end the life of someone who is suffering unbearably, who is beyond the help of medical science, and who has no hope of survival, is it not? This, of course, is the scenario most commonly presented when legalization of euthanasia is promoted. It should be stated without equivocation that such cases do indeed exist, and represent perhaps the most difficult circumstances in which to argue against euthanasia. But it should also be said that such cases are becoming far less common as pain management techniques and physician training in terminal care improve: in my experience, and in the experience of many of my peers who care for the terminally ill, is a rare occurrence indeed that a patient cannot have even severe, intractable pain managed successfully.

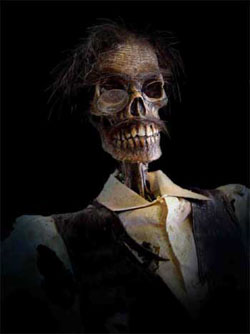

But the core arguments used in support of euthanasia in such dire circumstances are easily extended to other terminal situations–or situations not so very terminal at all. Intractable terminal pain merges seamlessly into hopeless prognosis, regardless of time frame; then flows without interruption to chronic diseases such as multiple sclerosis or severe disabilities. Once the principle of death as compassion becomes the guiding rule, the Grim Reaper will undergo metamorphosis into an angel of light, ready to serve one and all who suffer needlessly.

To mitigate the risk of this so-called “slippery slope,” it has been suggested that safeguards against such mission creep be crafted. Such measures may invoke mandatory second opinions, waiting periods, or committee review, prior to approval of an act of euthanasia. That such measures are ultimately doomed to fail is self-evident: in effect, they impose a roadblock between patient autonomy and relief of suffering and its amelioration through euthanasia–and thus run counter to the core principle sustaining it. It is not difficult to foresee that such roadblocks will quickly be made less “burdensome,” if not rendered utterly impotent, by relentless pressures to prevent patients from needlessly suffering, regardless of their underlying disease.

Perhaps more importantly, the process of assessing and approving an act of euthanasia through second opinions or committee review is not some ethically neutral decision, such as vetting budget items or inventory purchases. Those who serve in such advisory or regulatory capacity must by necessity be open to–indeed supportive of–the idea of euthanasia, lest all reviewed cases be denied. As demand for euthanasia increases, such approvals will become rubber-stamped formalities, existing solely to provide defensive cover for unrestricted assisted termination.

But such arguments against euthanasia are in essence process-oriented, and miss the much larger picture of the effects of individual euthanasia on our collective attitudes about life and death, and our societal constitution. There can be little question that the practice of actively terminating ill or dying patients will have a profound effect on the physicians who engage in this practice. The first few patients euthanized may be done in a spirit of compassion and mercy–but repetition deadens the soul and habitualizes the process. This is routinely seen in many areas of health care training and practice: the first cut of a novice surgeon is frightening and intimidating; the thousandth incision occurs with nary a thought. One’s first autopsy is ghoulish; the hundredth merely objective fact-finding. Euthanasia, practiced regularly, becomes simply another tool: this can be readily seen in the statistics from the Netherlands, where even 15 years ago, a startling percentage of reported cases of euthanasia by physicians took place without explicit patient request — reflecting far more a utilitarian attitude toward euthanasia than some diabolical conspiracy to terminate the terminal. The detached clinicians, utterly desensitized to the act of taking a life, now utilize it as they would the initiation of parenteral nutrition or the decision to remove a diseased gallbladder.

Such false assumptions about the objective impartiality of the decision-making process leading to euthanasia can be seen as well when looking at the family dynamics of this process. We are presented with the picture of the sad but compassionate family, quietly and peacefully coming to the conclusion that Dad–with his full assent, of course–should mercifully have his suffering ended with a simple, painless injection. Lost in this idyllic fantasy is the reality of life in families. Anyone who has gone through the death of a parent and the settlement of an estate knows first-hand the fault lines such a life crisis can expose: old grievances brought back to life, old hot buttons pushed, greed and avarice bubbling to the surface like a toxic witch’s brew. Does brother John want Dad’s dignified death so he can cop the insurance cash for his gambling habit? Does sister Sue, who hates her father and hasn’t spoken to him in years, now suddenly want his prompt demise out of genuine concern for his comfort and dignity? Are the children–watching the estate get decimated by the costs of terminal care–really being objective about their desire for Mom’s peaceful assisted death? And does Mom, who knows she’s dying, feel pressured to ask for the needle so she won’t be a burden to her children? Bitter divisions will arise in families who favor euthanasia and those who oppose it–whether because of their relationship, good or bad, with the parent, or their moral and ethical convictions. To make euthanasia the solution to difficult problems of death and dying, as suggested by its proponents, will instead require the death of our spirits: a societal hardness of heart whose effects will reach far and wide throughout areas of life and culture far beyond the dying process. Mercy killing will kill our mercy; death with dignity so delivered will leave us not dignified but degraded.

The driving force behind legalized euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide is patient autonomy: the desire to maintain control over the dying process, by which, is it hoped, we will maintain our personal dignity. But the end result of legalized euthanasia will instead, in many cases, be loss of patient autonomy. When legalized, medical termination of life will by necessity be instituted with a host of safeguards to prevent its abuse. Such safeguards will include restricting the procedure to those in dire straights: intolerable suffering, a few months to live, and the like. Inherent in these safeguards are the seeds of the death of patient autonomy: such determinations must rely on medical judgments–and therefore will ultimately lie in the hands of physicians rather than patients. It will be physicians who will decide what is intractable pain; it is physicians who will judge how long you have to live; it is physicians who will have the last say on whether your life has hope or is no longer worth living. Such decisions may well be contested–but the legal system will defer to the judgment of the health care profession in these matters. Patient autonomy will quickly become physician autocracy. For those who request euthanasia, it will be easy; for those who do not wish it, but fit the criteria, it will also be far too easy.

This has been the legal and practical evolution of euthanasia in the Netherlands. The legal progression from patient autonomy with safeguards to virtual absence of restrictions on euthanasia is detailed in a superb paper from Brooklyn Law School’s Journal of International Law (available here as a PDF), in which this evolution is detailed:

Soon after the Alkmaar case was decided, the Royal Dutch Medical Association (KNMG) published a set of due care guidelines that purported to define the circumstances in which Dutch physicians could ethically perform euthanasia.

The KNMG guidelines stated that, in order for a physician to respond to a euthanasia request with due care,

- The euthanasia request must be voluntary, persistent, and well-considered.

- The patient must suffer from intolerable and incurable pain and a discernible, terminal illness.

Thereafter, Dutch courts adopted the KNMG guidelines as the legal prerequisites of due care in a series of cases between 1985 and 2001. Despite the integration of the KNMG’s due care provisions, courts remained confused regarding what clinical circumstances satisfied the requirements of due care. In 1985, a court acquitted an anesthesiologist who provided euthanasia to a woman suffering from multiple sclerosis. The court thereby eliminated the due care requirement that a patient must suffer from a terminal illness. By 1986, courts decided that a patient need not suffer from physical pain; mental anguish would also satisfy the intolerable pain due care requirement.

Similarly, all reported prosecutions of euthanasia prior to 1993 involved patients who suffered from either physical or mental pain. Then, in the 1993 Assen case, a district court acquitted a physician who had performed active voluntary euthanasia on an otherwise healthy, forty-three year old woman. The patient did not suffer from any diagnosable physical or mental condition, but had recently lost both of her sons and had divorced her husband. With the Assen case, Dutch courts seemed to abandon the requirement that a patient suffer from intolerable pain or, for that matter, from any discernible medical condition as a pre-condition for the noodtoestand [necessity] defense.

The requisite ambiguity of all such safeguards will invariably result in their legal dilution to the point of meaninglessness–a process which increasingly facilitates the expansion not only of voluntary, but also involuntary euthanasia. This is inevitable when one transitions from a fixed, inviolable principle (it is always wrong for a physician to kill a patient) to a relative standard (you may end their lives under certain circumstances). The “certain circumstances” are negotiable, and once established, will evolve, slowly but inexorably, toward little or no standards at all. When the goalposts are movable, we should not be surprised when they actually get moved.

Another effect rarely considered by those favoring euthanasia is its effect on the relationship between patients and their physicians. The physician-patient relationship at its core depends upon trust: the confidence which a patient has that their physician always has their best interests at heart. This is a critical component of the medical covenant–which may involve inflicting pain and hardship (such as surgery, chemotherapy, or other painful or risky treatments) on the patient for their ultimate benefit. Underlying this trust is the patient’s confidence that the physician will never deliberately do them harm.

Once physicians are empowered to terminate life, this trust will invariably erode. This erosion will occur, even were involuntary euthanasia never to occur–a highly unlikely scenario, given the Dutch experience. It will erode because the patient will now understand that the physician has been given the power to cause them great harm, to kill them–with the full legal and ethical sanction of the law. And the knowledge of this will engender fear: fear that the physician may abuse this power; fear that he or she may misinterpret your end-of-life wishes; fear that he may end your life for improper motives, yet justify it later as a legal and ethical act. The inevitable occurrence of involuntary euthanasia–which in an environment of legalized voluntary euthanasia will rarely if ever be prosecuted–will only augment this fear, especially among the elderly and the disabled. In the Netherlands, many seniors carry cards specifying that they do not wish to have their lives terminated–a reflection of a widespread concern that such an occurrence is not uncommon, and is feared.

Montana judge: man has right to assisted suicide

Effects on physicians:

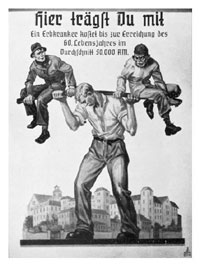

In the years following the Great War, a sense of doom and panic settled over Germany. Long concerned about a declining birth rate, the country faced the loss of 2 million of its fine young men in the war, the crushing burden of an economy devastated by war and the Great Depression, further compounded by the economic body blow of reparations and the loss of the German colonies imposed by the Treaty of Versailles. Many worried that the Nordic race itself was threatened with extinction.

In the years following the Great War, a sense of doom and panic settled over Germany. Long concerned about a declining birth rate, the country faced the loss of 2 million of its fine young men in the war, the crushing burden of an economy devastated by war and the Great Depression, further compounded by the economic body blow of reparations and the loss of the German colonies imposed by the Treaty of Versailles. Many worried that the Nordic race itself was threatened with extinction.

I hope to have more to say on the issue of euthanasia and assisted suicide in the near future. In the meantime, I highly recommend

I hope to have more to say on the issue of euthanasia and assisted suicide in the near future. In the meantime, I highly recommend  Often in the sturm und drang of a world gone mad, there comes, through the chaos and insanity, some brief moment of clarity. Such times pass by quickly, and are quickly forgotten — as this brief instance might have been, courtesy of my neighboring bell weather state of Oregon: (HT:

Often in the sturm und drang of a world gone mad, there comes, through the chaos and insanity, some brief moment of clarity. Such times pass by quickly, and are quickly forgotten — as this brief instance might have been, courtesy of my neighboring bell weather state of Oregon: (HT: