As many of you know, those of us living in the Northwest got battered by a pretty hefty windstorm last week. Packing gusts up to 60 mph (up to 100 mph out at the coast), the winds wreaked havoc with roads and especially power lines. After a very soggy November (15 1/2 inches of rain ), the ground was saturated, and fir trees — not known for their deep roots — started falling like crazy.

Their is an ancient tradition in the Northwest which maintains that most power lines must be strung above ground along streets lined by firs (an ancient Indian ritual, evidently) and hence when the winds blow, the power goes out on a big scale — over 1 million lost power in the Puget Sound area alone.

Once the trees hammer the wires, utility poles go down as well, causing lots of live wires on the ground and a real mess to repair.

We were fortunate to lose power only for about 36 hours — although cable (and therefore internet) are still out at home, with no timetable set to get it working again.

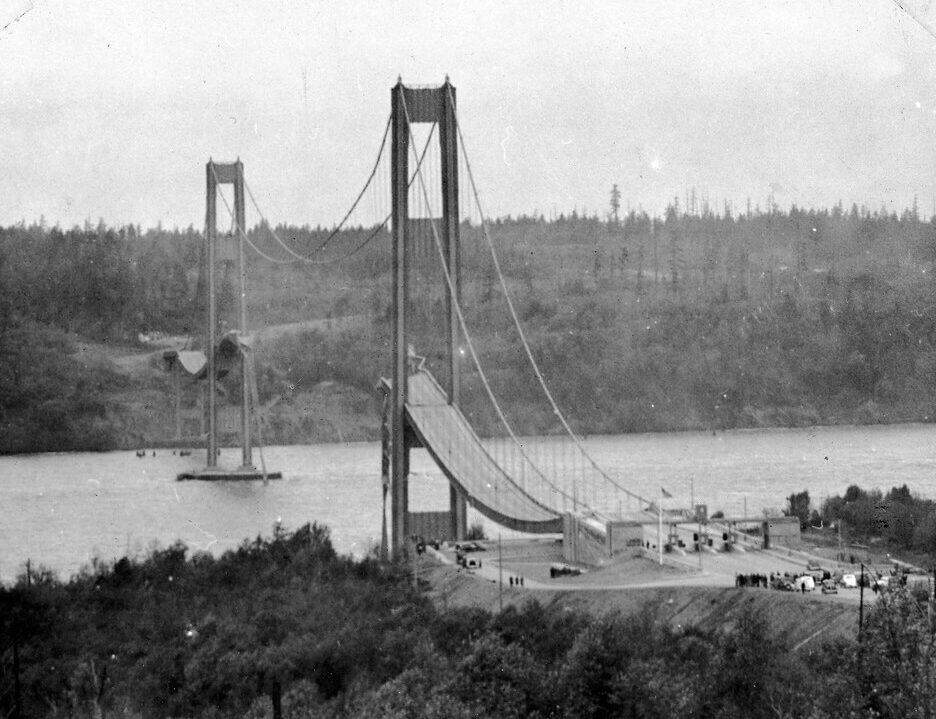

This is the kind of storm which brought down the first Narrows Bridge (aka Galloping Gerty)

The current bridge has withstood many such storms without a glitch — although it was closed for about 6 hours during the storm. The new bridge under construction suffered no damage as well, although temporary safety fences were pretty well shredded, and were dangling off the sides of the bridge the following day.

The current bridge has withstood many such storms without a glitch — although it was closed for about 6 hours during the storm. The new bridge under construction suffered no damage as well, although temporary safety fences were pretty well shredded, and were dangling off the sides of the bridge the following day.

With home internet out for the near future, I may be a bit behind on posts for a while, but there’s a couple in the chute not far from completion, so stay tuned.