A reader named Katherine recently e-mailed me. She had lost her husband, a man some years older than she, to multiple myeloma and Alzheimer’s disease. She is a Christian, and is struggling to make sense of his death, and the difficult questions of why God allows suffering. She writes, after giving me some details of his life, death, and fine character, and asks:

A reader named Katherine recently e-mailed me. She had lost her husband, a man some years older than she, to multiple myeloma and Alzheimer’s disease. She is a Christian, and is struggling to make sense of his death, and the difficult questions of why God allows suffering. She writes, after giving me some details of his life, death, and fine character, and asks:

Why does God allow such terrible illnesses to such a kind person? I know there is really no answer as I know all about Job. The thing I am really afraid is that I prayed for his healing, and it did not happen. When I became a Christian back in the 80’s, the health and prosperity gospel was big at the time, and I guess it really influenced me more than I care to admit as I now know it is false. Even though I know it is false, I have become obsessed that God did not answer my prayer because of not being able to get rid of all the sin in my life (as if this were possible to do). One of the teachings of that movement was that if your prayer for healing went unanswered it was either because of lack of faith or sin in your life. I kept thinking that I don’t always put God first in my life, and that I spent more time reading secular magazines than reading my Bible and listening to more secular music than Christian music. These were my “main” sins, at least in my mind and thinking. Can you shed some light on this for me? I would be very appreciative.

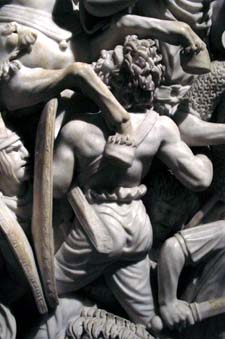

The problem of suffering and evil is an ageless one. It poses a particular challenge for Judaism and Christianity, because of the seemingly insoluble tension between a world filled with suffering and evil, and the belief in a God who is good and all-powerful. Solutions to this dilemma, both adequate and inadequate, abound. It is the desperate hope of the atheist that this logical incompatibility proves beyond question the nonexistence of God. Others, less willing to ditch a Divine order, have concluded that God is good, but impotent; or that God is detached and uncaring, or capricious, or moody, or sadistic — and therefore not good.

It must be said plainly that answers to this paradox are neither simple nor entirely satisfactory. The dilemma as it stands may be solved in a global and satisfactory way — as has been done by both Judaism and Christianity — but invariably the lofty principles seem to break down at the moment when a solution is most needed: in the time of crisis when we ourselves experienced the depths, hopelessness, and irrationality of suffering in our own lives. CS Lewis, whose tightly reasoned treatise The Problem of Pain provides an extraordinarily deep and thorough discussion of this dilemna–later in life nearly repudiates his faith and sound theology after the death of his wife, a process painfully detailed in his diaries, A Grief Observed. It is indeed unsettling to watch Lewis discard all of his carefully reasoned and theological understandings of pain and suffering in the brutal crucible of unbearable pain and loss. Nonetheless, he ultimately comes to terms with the paradox, and undergoes an embracing of this profound dilemma far deeper than the intellectual by means of his own trial of fire.

At the heart of this difficult issue lies the human heart. God undertook a vast and dangerous experiment when creating man: He wanted, not merely another animal — of which there were countless — but an animal capable of something He alone understood: love. He gave this exalted animal vast intellect — but this was not sufficient to engender love. He gave His creation powerful emotions, the capacity for both creation and destruction, which He alone had possessed — but this also was not sufficient. For love — the utter, uninhibited emptying of self for another — required that most dangerous license of all: free will. Having created us thus, designed with the capacity to love, we must of necessity be utterly free to choose — for choice is the very heart, the very essence of love.

It was, by all visible measures, an experiment gone wildly awry. Having given this creature the extraordinary capabilities required to love fully — intellect, emotion, passion, empathy, the ability to feel intense pleasure and pain both physically and spiritually — he set this creature free to love — first of all Himself, and then others of like kind. And the first choice of this masterpiece of creation was the decision to turn away: to replace the intended objects of love with the sterile altar of self. Thus was unleashed the monstrous liability of a truly free creature: the ability to hate, to cause pain, to kill, to destroy.

A world in which God eliminated evil would by necessity be emptied of all mankind.

If we are to be honest, much of the pain and suffering which comprise the evil of the world is due to nothing more than this: that man, having been given the ability to choose, chooses wrongly, and uses the gifts and abilities given for the purpose of love to instead elevate himself at the expense of others, often in ways stunningly malicious and utterly wicked. Look around you, at the world both near and far: pride, selfishness, greed, lust, rage, jealousy — all these things manifest themselves in our lives and those of others, causing great pain and endless suffering. The child abused; the wife abandoned; the drive-by shooting; the greedy CEO who bankrupts the company and rapes the stockholders; the serial killer and the rapist; genocide; wars of conquest; torture; senseless massacres: these are the actions of men and women putting self above others — and each of us does it, to a greater or lesser degree, though we minimize our own roles to justify our own actions. We all wish for a world where God would eliminate evil — but all assume that we ourselves would be the only ones left standing when His judgment is delivered. A world in which God eliminated evil would by necessity be emptied of all mankind.

Yet there also exists those evils which have been called, in days past, somewhat ironically, “acts of God” — those circumstances or events which cause pain and suffering, not directly engendered by human evil. Thus the child is born with a severe birth defect; hurricanes, earthquakes, and tornadoes cause death and destruction; chronic and devastating diseases fall upon those who seemingly deserve a far better fate. It is with this, this seemingly capricious evil, with which we struggle most earnestly, straining to understand, yet to no avail.

Judaism and Christianity both imply that some such evil may be consequential, the result of punishment or predictable consequences for the malfeasance of man. A more robust theology is less accusatory and thereby more coarsely granular — maintaining that such evil has entered the world because of the fall of man. Under such design our divine divorce has corrupted not only behavior, but our very natures, and all of creation. Yet such theology is of little comfort to those who are the objects of such seemingly random evil; we demand to know of God, “Why?” — and in particular, “Why me?” Yet there is no answer forthcoming, and we are left assuming a God either powerless to stop such evil or unwilling to do so.

Yet the problem of a good God, an omnipotent God, and an evil world of His creation is not entirely insoluble. Much lies in our projection of human frailty onto the nature of the Divine, and the impreciseness of our definitions of good and omnipotent. When we say God is good, we tend to mean that God is “nice” — that he would never do anything to cause us pain or suffering. Yet even in our limited experience, we must acknowledge that pain and suffering, while not inherently good, may be a means to goodness. We choose to have surgery or chemotherapy, though painful and debilitating, that our cancer may be cured. The halls of Alcoholics Anonymous are filled with men and women who, having faced both personal and relational destruction, have used their former liabilities as a gateway to a new, more fulfilling life — one which could not have taken place apart from their harrowing journey through alcoholism. To a misbehaving child, the discipline of a loving father is not perceived as good, but such correction is essential for the development of personal integrity, social integration, and responsibility.

Our inability to discern the potential for good in pain and suffering does not by necessity deny its presence; there are many who, when asked, will point to painful, difficult, and unbearable times in life which have brought about profound, often unexpected good in their lives, unforeseeable in the midst of their dark days. There surely is much suffering which defies our capacity to understand, even through we strive with every fiber of our being to find the goodness therein. But the fact that such inexplicable suffering exists, and that answers are often lacking, does not preclude the possibility that God is good, or that such suffering may ultimately lead to something greater and more noble than the pain endured.

We are … not merely imperfect creatures that need improvement: we are rebels that need lay down their arms

In our egocentricity we often neglect to look for the benefit in our suffering which comes not to us, but rather to others. Caring for someone suffering unbearably provides an opportunity to the caretaker to experience selfless love, compassion, tenderness, patience and endurance — character traits sadly lacking in our selfish world, which routinely turns its back on suffering to pursue an untroubled life of self-fulfillment and self-gratification. It is not inherently evil to be called to give beyond our means and ability — as caring for someone suffering always demands — for in the exhaustion and inadequacy thus revealed, we may discover unknown inner strengths, and come to a richer, and more fulfilling dependence on God. We are, as CS Lewis so accurately described, “not merely imperfect creatures that need improvement: we are rebels that need lay down their arms” — and finding how shallow are our reserves of love, compassion, and strength, we may through this brokenness seek to acquire them, humbly, from their Source.

But surely an omnipotent God has the power to stop suffering — is He not either impotent or evil when failing to use such power to remove our suffering? The omnipotence of God, like His goodness, is but dimly perceived. For the power of God is in perfect harmony with the purpose of God, and is thus used to advance these purposes for the greater good. Thus, the good deed of creating man with free will — and thereby capable of love — by its very nature restrains the omnipotence of God to violate that free will. The evil of the world exists in large part, if not wholly, because this free will has been abused. Yet the abuse of free will must be permitted, that the proper use of free will — the laying down of arms, the surrender to the sovereignty of a wholly good God — may take place, freely and unfettered as required by love. God must tolerate the existence of suffering and evil, that all may have the freedom to choose the good — though many will refuse to do so.

Yet he does not merely tolerate the presence of suffering, but provides for its very redemption: that suffering, though itself evil, may ultimately produce good. Thus pain, suffering, death, and evil need not triumph: they may provide the means that some may turn toward the good, or bring forth further good for themselves or others. This is redemption: to buy back that which is destructive, worthless, of no value, evil, and make it worthwhile, valuable, even priceless.

Christianity, throughout its history, has struggled with and largely resolved the problem of pain, within the confines of the mystery of God. Yet Christianity in its many doctrinal eddies has sometimes chosen the wrong path and the wrong answers to this challenge. Such errors generally fall into two broad categories: the concept of suffering as punishment or retribution from God, and the manipulation of God for man’s gratification. The first of these runs counter to the core doctrine of the cross: that God has chosen to provide in Christ a sacrificial lamb — that Christ, through his suffering, may bear the justice of God, so that we may see the mercy of God. Our suffering is not a punishment for sin, as such punishment negates the purpose of the cross. Correction, it may be; discipline, it often is; opportunity, it always is; punishment, it never is.

The countering position — that of God as divine opiate, ever present to kill our pain — is a variant of the faith which has become perniciously widespread, feeding on a culture of ease and self-gratification which creates God in its own image. Thus God becomes a font of wealth, of health, of prosperity, of a trouble-free materialistic lifestyle, a divine vending machine whose coinage is faith. Faith, however, in such a worldview is no longer a profound trust in a God who is beyond understanding and infinitely wise, but becomes instead a means of buying from God all which we demand. Hence, we may be wealthy, if we only have enough faith; we may be healed, if our faith is sufficient; we will not suffer if we will but strengthen and enlarge our faith. Our faith must be prefect, lest our pleas go unheard. The strength of faith matters more than its verity; we charge the gates of heaven with the bludgeon of self-will.

The perniciousness and destructiveness of this perversion of historical Christian faith lies in removing from the hands of God decisions of life and death, health and illness, wholeness and suffering, while burdening us with the hopeless demand that we steel our faith to impossible heights to coerce and manipulate the will of God. That such efforts are typically fruitless seems self-evident: God most surely is capable of healing — and does indeed do so often, even dramatically at times — but most surely does so in accordance with his divine wisdom and will. Should His wisdom dictate that suffering, poverty, brokenness, even death and despair would better serve the purposes of drawing men to Himself, what measure of human obstinacy and recalcitrance will change this will? When such “faith” proves futile, it destroys trust in God, and not infrequently leads to utter loss of belief, a bitter agnosticism born in false expectations and misplaced hope.

We demand of God that which we alone deem to be good, then blame Him when He pursues a greater good beyond our understanding

Hence, we demand of God that which we alone deem to be good, then blame Him when He pursues a greater good beyond our understanding. This is the struggle to which Kathleen is alluding, as she questions the goodness of God in failing to heal her husband, blaming her own “sins” for his untimely demise. To us, such a healing seems only good — in so far as it mitigates our pain and loss, as well as that of those we love — but like the surgeon’s knife, sometimes such pain must not be withheld that evil may be conquered by the good. Were he healed, and restored to full health, would he not then face death on yet another day? Our lives have both purpose and a proper time: we live for that purpose, and we die when that purpose is fulfilled. That those who are left behind cannot grasp that purpose — and appropriately suffer profound pain and loss at this separation — does not negate that purpose nor impede its culmination.

We live in a time when our expectations of health, of prosperity, of a pain-free life are increasingly met in the physical realm, while we progressively become sickly, impoverished, and empty in the realm of the spirit. Despite our longer lives, we live in dread of death; despite our greater health, we obsess about our ills; despite our comfortable lives, we ache from an aimlessness and purposelessness which eats at our souls and deadens our spirits. Though we have at our command the means to kill our pain–to a degree never before seen in the history of the world–yet we have bargained away our peace in pursuit of our pleasure. The problem of pain has never been an easy one; in our day, it has not been solved, but rather worsened, by our delusions of perpetual comfort and expectations of a trouble-free life.

Until we come to terms with suffering, we will not have comfort; until we embrace our pain, peace will never be ours.

Roger L. Simon recently had an epiphany. While reporting from the Durban II conference, he encountered the face of evil: President Ahmadinejad of Iran. He describes this encounter thus:

Roger L. Simon recently had an epiphany. While reporting from the Durban II conference, he encountered the face of evil: President Ahmadinejad of Iran. He describes this encounter thus: I am not easily shocked anymore.

I am not easily shocked anymore.

David Brooks, in a NY Times Op-Ed piece after the

David Brooks, in a NY Times Op-Ed piece after the