A wise friend–a man who helped me emerge from a period of considerable difficulty in my life–once taught me a simple lesson. In less than a minute, he handed me a gift which I have spent years only beginning to understand, integrating it into my life with agonizing slowness. It is a lesson which intellect cannot grasp or resolve, which faith only begins to illuminate–a simple principle which I believe lies close to the root of the human condition.

My friend taught me a simple distinction: the difference between

guilt and

shame.

While you no doubt think I am devolving into the linguistic morass of terminal psychobabble, I ask you to stick with me for a few moments. What you may discover is a key to understanding religion, terrorism, social ills such as crime and violence–and why the jerk in the next cubicle pushes your buttons so often. On the other hand, if you’re among those who believe guilt and shame are simply the tools of religion and society to restrict your freedom–that as a perfectly liberated postmodern person you are beyond all that–well, you are probably wasting your time reading this. But most of us recognize the influence of guilt and shame in our lives–even while trying not to focus on them, as they are uncomfortable emotional topics, best avoided if possible.

There is a tendency to conflate guilt and shame, merging them into a single human response to bad behavior or personal shortcomings. Yet they are quite different.

Guilt is about

behavior,

shame about

being. Allow me to expand on this a bit.

Guilt is an emotional–or some would say spiritual– human response to behavior or actions which violate a respected set of rules. The rules violated may be internal or external, and may be based either in reality and truth or distortion and error. The rules which may engender guilt must be

respected: that is, they must originate from a valid source of authority–parents, elders, religion, law–or have been internalized into one’s personal mores or conscience from one or more such sources. Rules which are

not respected pose no difficulty: I feel no guilt at not becoming a suicide martyr for Allah, since I do not respect (i.e. recognize as valid) the rules which promote such behavior. The response to violating respected rules is at its heart based on

fear: fear of punishment by God or man, fear of rejection, or fear of ostracization from friends, family, or society.

Since guilt is an uncomfortable emotional state, we generally make efforts to avoid or mitigate it if possible. There are a number of means by which this can be accomplished, with greater or lesser efficacy. We may of course, practice

avoidance of the behavior which induces the guilt. If the rules are legitimate and based on worthwhile principles, this is obviously a beneficial approach: if you don’t steal things, you won’t go to jail for burglary. But avoidance may prove destructive if the rules are based on error. For example, if your parents or religion have taught you that all sexual activity is wrong or evil, this can prove a huge impediment to physical intimacy and relationships in marriage.

Guilt may also be mitigated–especially when it is chronic and recurring–by

changing the rules. You may leave a religion which is highly legalistic for another less so–or for none at all; you may change your situation or environment to one where the rules can be ignored and not enforced; you may seek counseling to correct perceptions about sexuality or other destructive interpersonal biases or beliefs. Or you may simple practice

denial–justifying your behavior through the creation of new internal or social rules, while avoiding or rationalizing the inevitable consequences of your still-errant behavior.

So guilt may be addressed by modifying behavior or changing belief systems, through choice or denial. What then about shame?

Shame–the very word makes us uneasy, striking deeply into the core of our being. For shame is not about what we do, but about

who we are. It speaks to a deep sense of unworthiness, rejection, inadequacy, and isolation. It says we are not OK, that what we truly are must be hidden. And this we do with all the energy at our disposal, throwing up an impenetrable wall to keep others out at all costs. For the essence of shame is

relational–it says that if you

really knew what I was like, you would be repulsed and thus reject me. The resulting isolation–real or perceived–is a devastating threat, engendering a pain so profound it approaches unbearable.

The origins of shame are varied, and not fully understood. We seem to be programmed to interpret certain words and behavior by others–especially parents and siblings in childhood–as not simply critical of our behavior, but a statement of our

worth. This is an especially powerful force coming from parents, under whose authority and supervision we are molded into social beings. While this may be especially pronounced in dysfunctional or abusive homes–alcoholism, sexual abuse, and mental illness come to mind–it occurs even in well-functioning family units, and with speech and actions which are not intended as critical or demeaning, but which are

interpreted as such. The soil of the soul seems fertile ground to bring forth a tainted crop of shame, even from the seemingly benign bruises of normal human interactions and relationships.

From the Judeo-Christian perspective, this propensity toward shame is understood as rooted in the spiritually-inherited rupture of our relationship with God, manifesting itself in an extreme self-centeredness and self-focus, which acts as a toxic filter letting in the destructive while keeping out the good. Having been born into a state of remoteness from God–perceived at a spiritual level as rejection by Him, though in fact just the opposite–we are acutely sensitized to rejection by others: it fits the mold perfectly. Thus every real or perceived hurt, criticism, or rejection simply confirms that we

are rejected, worthless, and of no value. Our self-centered mindset insures that even events not focused on our self-value are interpreted in ways that affirm our sense of shame–hence the child that blames herself for her father’s drinking and abusiveness.

While shame lives deep below the surface–a monstrous child kept hidden from public view–its manifestations are legion, and its ability to percolate to the surface and alter our lives and behavior is formidable. The pain of shame requires response, no less than a hand on a hot stove, and it may be triggered by many means: by concerns about physical size, strength, skill, or ability; by issues of dependency or independence; by competition with others; by worries about personal attractiveness and sexuality; or when dealing with matters of personal closeness and intimacy. Thus triggered, an outward manifestation is inevitable, and will generally fall into one of these areas:

- Withdrawal — perhaps the most natural response to pain, we retreat from its source to avoid the risk of exposing our vulnerability. Hence we steer clear of people or circumstances which may trigger shame, withdrawing into a nominally safer–but profoundly lonely–world. This response may range in manifestation from shyness up to deep, pathologic depression or psychosis.

- Attack the Self — The loneliness of withdrawal and isolation is itself a deeply uncomfortable state, and often raises the profound terror of abandonment. To avoid such painful estrangement, many will resort to demeaning and depreciating themselves, thereby becoming subservient to others more powerful, resulting in a condition of dependency. While this may lessen the pain of isolation and abandonment, it further exacerbates the underlying shame by reinforcing one’s worthlessness and inferiority. The relationships so formed are not those of equals, and therefore satisfy the need for true intimacy poorly. Such responses range from obsequiousness and self-demeaning deference to others, to depression, and all the way to masochism, self-mutilation, and suicide.

- Avoidance — If the shame cannot be eliminated, the feelings most surely can: shame is soluble in alcohol, can be freebased, and its pain assuaged as well by a host of other self-destructive behaviors. One’s choice of drug–chemical or behavioral–is influenced by genetics, neurochemistry, and environment, but all have the common goal of emotional oblivion. Eating disorders, obsessive-compulsive behavior, behavioral addictions to work, computers, gambling, or sex can divert the mind and stimulate sufficient endorphins to make the pain go away–at least for the moment. But the drugs and behaviors only worsen the underlying sense of failure and inadequacy, and lead to fractured and destroyed relationships, loneliness, and sometimes physical illness and death.

- Attack Others — Rage and anger are common responses to shame, as we seek to defend our threatened worth by destroying the antagonist–or at least diminishing their worth, through sarcasm, criticism, gossip, physical, verbal or sexual abuse, or violence. But as with other coping mechanisms for shame, the outcome is invariably destroyed relationships, and adverse consequences, both legal and personal.

Thus the engine of shame drives a host of behaviors which are both personally destructive and socially disruptive. If you scratch the surface of nearly any dysfunctional personal or social problem–alcoholism and drug abuse, obesity, international terrorism–you will find at its dark heart the issue of shame. It is, at the very least, a common thread among such societal and personal liabilities, if not a central driving force.

So it behooves us to get a handle on this matter of shame, uncomfortable though it may be. Our responses to its provocations are major causes of personal agony and social crisis. But like a schoolyard bully, once confronted face-to-face, the tyranny of shame can be broken through courage and openness, and the strength of numbers. On these thoughts I will be reflecting in a subsequent essay.

Ancient wisdom: a sage injunction uttered in a time when simple shepherds and farmers parsed out land for grazing and grain, speaking to the prudence of respecting contracts, negotiated agreements with those with whom we live, to abide in a measure of peace. Be honest; respect the property and possessions of those with whom you must abide; do not trade peaceful relations for parcels of land.

Ancient wisdom: a sage injunction uttered in a time when simple shepherds and farmers parsed out land for grazing and grain, speaking to the prudence of respecting contracts, negotiated agreements with those with whom we live, to abide in a measure of peace. Be honest; respect the property and possessions of those with whom you must abide; do not trade peaceful relations for parcels of land. In my previous post on guilt and shame, I discussed their nature and differences, their impact on personal and social life, and their instrumentality in much of our individual unhappiness and communal dysfunction. If indeed shame is the common thread of the human condition–fraught as it is with pain, suffering, and evil–it must be mastered and overcome if we are to bring a measure of joy to life and peace to our spirits and our social interactions.

In my previous post on guilt and shame, I discussed their nature and differences, their impact on personal and social life, and their instrumentality in much of our individual unhappiness and communal dysfunction. If indeed shame is the common thread of the human condition–fraught as it is with pain, suffering, and evil–it must be mastered and overcome if we are to bring a measure of joy to life and peace to our spirits and our social interactions.

A wise friend–a man who helped me emerge from a period of considerable difficulty in my life–once taught me a simple lesson. In less than a minute, he handed me a gift which I have spent years only beginning to understand, integrating it into my life with agonizing slowness. It is a lesson which intellect cannot grasp or resolve, which faith only begins to illuminate–a simple principle which I believe lies close to the root of the human condition.

A wise friend–a man who helped me emerge from a period of considerable difficulty in my life–once taught me a simple lesson. In less than a minute, he handed me a gift which I have spent years only beginning to understand, integrating it into my life with agonizing slowness. It is a lesson which intellect cannot grasp or resolve, which faith only begins to illuminate–a simple principle which I believe lies close to the root of the human condition.

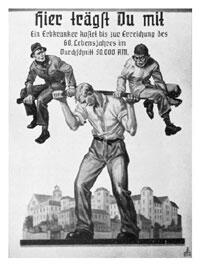

In the years following the Great War, a sense of doom and panic settled over Germany. Long concerned about a declining birth rate, the country faced the loss of 2 million of its fine young men in the war, the crushing burden of an economy devastated by war and the Great Depression, further compounded by the economic body blow of reparations and the loss of the German colonies imposed by the Treaty of Versailles. Many worried that the Nordic race itself was threatened with extinction.

In the years following the Great War, a sense of doom and panic settled over Germany. Long concerned about a declining birth rate, the country faced the loss of 2 million of its fine young men in the war, the crushing burden of an economy devastated by war and the Great Depression, further compounded by the economic body blow of reparations and the loss of the German colonies imposed by the Treaty of Versailles. Many worried that the Nordic race itself was threatened with extinction.

I have been struck by the evisceration of language in our contemporary culture, and wonder about its implications. We humans can communicate by many means – by touch, by expressions, by giving — even by our mere presence in situations where we would be more comfortable elsewhere, such as when sharing grief or loss with another. But our primary means of communication is by language.

I have been struck by the evisceration of language in our contemporary culture, and wonder about its implications. We humans can communicate by many means – by touch, by expressions, by giving — even by our mere presence in situations where we would be more comfortable elsewhere, such as when sharing grief or loss with another. But our primary means of communication is by language.