In the years following the Great War, a sense of doom and panic settled over Germany. Long concerned about a declining birth rate, the country faced the loss of 2 million of its fine young men in the war, the crushing burden of an economy devastated by war and the Great Depression, further compounded by the economic body blow of reparations and the loss of the German colonies imposed by the Treaty of Versailles. Many worried that the Nordic race itself was threatened with extinction.

In the years following the Great War, a sense of doom and panic settled over Germany. Long concerned about a declining birth rate, the country faced the loss of 2 million of its fine young men in the war, the crushing burden of an economy devastated by war and the Great Depression, further compounded by the economic body blow of reparations and the loss of the German colonies imposed by the Treaty of Versailles. Many worried that the Nordic race itself was threatened with extinction.

The burgeoning new sciences of psychology, genetics, and medicine provided a glimmer of hope in this darkness. An intense fascination developed with strengthening and improving the nation through Volksgesundheit–public health. Many physicians and scientists promoted “racial hygiene” – better known today as eugenics. The Germans were hardly alone in this interest – 26 states in the U.S. had forced sterilization laws for criminals and the mentally ill during this period; Ohio debated legalized euthanasia in the 20’s; and even Oliver Wendall Holmes, in Buck v. Bell, famously upheld forced sterilization with the quote: “Three generations of imbeciles are enough!” But Germany’s dire circumstances and its robust scientific and university resources proved a most fertile ground for this philosophy.

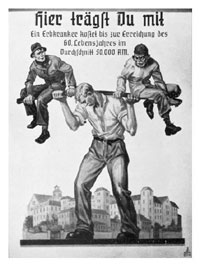

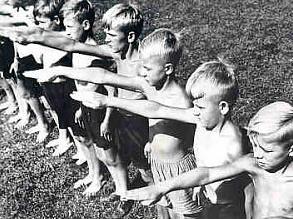

These novel ideas percolated rapidly through the social and educational systems steeped in Hegelian deterministic philosophy and social Darwinism. Long lines formed to view exhibits on heredity and genetics, and scientific research, conferences, and publication on topics of race and eugenics were legion. The emphasis was often on the great burden which the chronically ill and mentally and physically deformed placed on a struggling society striving to achieve its historical destiny. In a high school biology textbook – pictured above – a muscular German youth bears two such societal misfits on a barbell, with the exhortation, “You Are Sharing the Load!–a hereditarily-ill person costs 50,000 Reichsmarks by the time they reach 60.” Math textbooks tested students on how many new housing units could be built with the money saved by elimination of long-term care needs. Parents often chose euthanasia for their disabled offspring, rather than face the societal scorn and ostracization of raising a mentally or physically impaired child. This widespread public endorsement and pseudo-scientific support for eugenics set the stage for its wholesale adoption — with horrific consequences — when the Nazi party took power.

The Nazis co-opted medicine fully in their pursuit of racial hygiene, even coercing physicians in occupied countries to provide health and racial information on their patients to occupation authorities, and to participate in forced euthanasia. In a remarkably heroic professional stance, the physicians of the Netherlands steadfastly refused to provide this information, forfeiting their medical licenses as a result, and no small number of physicians were deported to concentration camps for their principled stand. As a testimony to their courage and integrity, not a single episode of involuntary euthanasia was performed by Dutch physicians during the Nazi occupation.

Would that it were still so.

The Netherlands was the first country in the world in which euthanasia and assisted suicide was legally performed, having fully legalized the practice in 2006 after several decades of widespread illegal–but universally unpunished–practice. The Dutch have come into the public consciousness periodically over the past 30vyears, initially with the consideration of assisted suicide laws in Oregon, Washington, Michigan and elsewhere in the early 90’s, and again with their formal legalization of physician-assisted suicide and euthanasia in 2001. Once again they are on the ethical radar, with the disclosure last week of the Groningen Protocol for involuntary euthanasia of infants and children.

The Groningen Protocol is not a government regulation or legislation, but rather a set of hospital guidelines for involuntary euthanasia of children up to age 12:

The Groningen Protocol, as the hospital’s guidelines have come to be known, would create a legal framework for permitting doctors to actively end the life of newborns deemed to be in similar pain from incurable disease or extreme deformities.

The guideline says euthanasia is acceptable when the child’s medical team and independent doctors agree the pain cannot be eased and there is no prospect for improvement, and when parents think it’s best.

Examples include extremely premature births, where children suffer brain damage from bleeding and convulsions; and diseases where a child could only survive on life support for the rest of its life, such as severe cases of spina bifida and epidermosis bullosa, a rare blistering illness.

The hospital revealed last month it carried out four such mercy killings in 2003, and reported all cases to government prosecutors. There have been no legal proceedings against the hospital or the doctors.

While some are shocked and outraged at this policy of medical termination of sick or deformed children (the story has been widely ignored by the mainstream media, and has gotten only limited attention on the Internet), it is merely a logical extension of a philosophy of medicine widely practiced and condoned in the Netherlands for many years, much as it was in Germany between world wars. It is a philosophy where the Useful is the Good, whose victims are the children whom Reason scorned.

Euthanasia is the quick fix to man’s ageless struggle with suffering and disease. The Hippocratic Oath — taken in widely varying forms by most physicians at graduation — was originally administered to a minority of physicians in ancient Greece, who swore to prescribe neither euthanasia nor abortion — both common recommendations by healers of the age. The rapid and widespread acceptance of euthanasia in pre-Nazi Germany occurred because it was eminently reasonable and rational. Beaten down by war, economic hardship, and limited resources, logic dictated that those who could not contribute to the betterment of society cease being a drain on its lifeblood. Long before its application to ethnic groups and enemies of the State, it was administered to those who made us most uncomfortable: the mentally ill, the deformed, the retarded, the social misfit. While invariably promoted as a merciful means of terminating suffering, the suffering relieved is far more that of the enabling society than of its victims. “Death with dignity” is the gleaming white shroud on the rotting corpse of societal fear, self-interest and ruthless self-preservation.

It is sobering and puzzling to ponder how the profession of medicine – whose core article of faith is healing and comfort of the sick – could be so effortlessly transformed into a calculating instrument of judgment and death. It is chilling to read the cold scientific language of Nazi medical experiments or Dutch studies on optimal techniques to minimize complications in euthanasia. Yet this devolution of medicine, with some contemplation, is not hard to discern. It is the natural gravity of man detached from higher principles, operating out of the best his reason alone has to offer, with its inevitable disastrous consequences. Contributing to this march toward depravity:

♦ The power of detachment and intellectualization: Physicians by training and disposition are intellectualizers. Non-medical people observing surgery are invariably squeamish, personalizing the experience and often repulsed by the apparent trauma to the patient. Physicians overcome this natural response by detaching themselves from the personal, and transforming the experience into a study in technique, stepwise logical processes, and fascination with disease and anatomy. Indeed, it takes some effort to overcome this training to develop empathy and compassion. It is therefore a relatively small step with such training to turn even killing into another process to be mastered.

♦ The dilution of personal responsibility: In Germany, the euthanasia of children was performed with an injection of Luminal, a barbiturate also used for seizures and sedation of the agitated. As a result, it was difficult to determine who was personally responsible for the deed: was it the nurse, who gave too much? The doctor, who ordered too large a dose? Was the patient overly sensitive to the drug? Was the child merely sedated, or in a terminal coma? Of course, all the participants knew what was going on, but responsibility was diluted, giving rationalization and justification full reign. The societal endorsement and widespread practice of euthanasia provided additional cover. When all are culpable, no one is culpable.

♦ Compartmentalization: an individual involved in the de-Baathification of Iraq said the following:

There is a duality in Baathists. You can find a Baathist who is a killer, but at home he’s completely normal. It’s like they split their day into two twelve-hour blocks. When people say about someone I know to be a Baathist criminal, ‘No, he’s a good neighbor!’, I believe him.

Humans have the remarkable ability to utterly separate disparate parts of their lives, to accommodate cognitive dissonance. Indeed, there is probably no other way to maintain sanity in the face of enormous personal evil.

♦ The banality of evil: Great evil springs in countless small steps from lesser evil. Jesus Christ was doubtless not the first innocent man Pilate condemned to death; soft porn came before child porn, snuff films, and rape videos; in the childhood of the serial killer lies cruelty to animals. Small evils harden the heart, making greater evil easier, more routine, less chilling. We marvel at the hideousness of the final act, but the descent to depravity is a gentle slope downwards.

♦ The false optimism of expediency: Solve the problem today, deny any future consequences. We are nearsighted creatures in the extreme, seeing only the benefits of our current actions while dismissing the potential for unknown, disastrous ramifications. When Baby Knauer, an infant with blindness, mental retardation and physical deformities, became the first child euthanized in Germany, who could foresee the horrors of Auschwitz and Dachau? We are blind to the horrendous consequences of our wrong decisions, but see infinite visions of hope for their benefits. As a child I watched television shows touting peaceful nuclear energy as the solution to all the world’s problems, little imagining the fears of the Cuban missile crisis, Chernobyl and Three Mile Island, the minutes before midnight of the Cold War, and the current ogre of nuclear terrorism.

Reason of itself is morally neutral; it can kill children or discover cures for their suffering and disease. Reason tempered by humility, faith, and guidance by higher moral principles has enormous potential for good – and without such restraints, enormous potential for evil.

The desire to end human suffering is morally good. Despite popular misconception, the Judeo-Christian tradition does not view suffering as something good, but rather something evil which exists, but which may be transformed and redeemed by God and grace, to ultimately produce a greater good. This is a difficult sell to a materialistic, secular world, which does not accept the transformational power of God or the existence of spiritual consequences, or principles higher than human reason.

Yet the benefits of suffering, subtle though they may be, can be discerned in many instances even by the unskilled eye. What are the chances that Dutch doctors will find a cure for the late stage cancer or early childhood disease, when they now so quickly and “compassionately” dispense of their sufferers with a lethal injection? Who will teach us patience, compassion, unselfish love, endurance, tenderness, and tolerance, if not those who provide us with the opportunity through their suffering, or mental or physical disability? These are character traits not easily learned, though enormously beneficial to society as well as individuals. How will we learn them if we liquidate our teachers?

Higher moral principles position roadblocks to our behavior, warning us that grave danger lies beyond. When in our hubris and unenlightened reason we crash through them, we do so at great peril, for we do not know what evil lies beyond. The Netherlands will not be another Nazi Germany, as frightening as the parallels may be. It will be different, but it will be evil in some unpredictable way, impossible to foresee when rationalism took the first step across that boundary to kill a patient in mercy.

Newsweek has declared:

Newsweek has declared:

In the past several days, through the lens of my profession, I have been given a rather stark and disturbing vision of our current cultural revolution. It is, it seems, a revolution every bit as pervasive and transformational — and destructive — as China’s Cultural Revolution of the 60s — and indeed may be but a different manifestation of a global transformation which transpired in those very same decades in the West. Ideas have consequences, as they say, and we are watching them bear fruit before our very eyes in a slow-motion train wreck which seems now to be accelerating at a disturbing rate.

In the past several days, through the lens of my profession, I have been given a rather stark and disturbing vision of our current cultural revolution. It is, it seems, a revolution every bit as pervasive and transformational — and destructive — as China’s Cultural Revolution of the 60s — and indeed may be but a different manifestation of a global transformation which transpired in those very same decades in the West. Ideas have consequences, as they say, and we are watching them bear fruit before our very eyes in a slow-motion train wreck which seems now to be accelerating at a disturbing rate.

A recent post on the worldview of contemporary postmodern liberalism was kindly linked by Gerard Vanderleun over at

A recent post on the worldview of contemporary postmodern liberalism was kindly linked by Gerard Vanderleun over at