A recent post on evil brought some very thoughtful comments, which meandered a bit, as comment threads are wont to do, onto the topic of forgiveness.

A recent post on evil brought some very thoughtful comments, which meandered a bit, as comment threads are wont to do, onto the topic of forgiveness.

It is a topic I have visited before, and no doubt will visit many times again, in experience if not in writing. The issue of forgiveness is ever fresh in human experience, flowing inevitable from the wanton harms and evil which surrounds us and so often affects us directly. It is a subject among Christians which engenders a great deal of misunderstanding and sometimes foolishness. In what is certainly the most uttered prayer in Christianity — the Lord’s Prayer — we are called to both ask forgiveness for ourselves and extend it to others: “Forgive us our trespasses, as we forgive those who trespass against us.”

So what exactly is forgiveness?

Forgiveness requires, first of all, that there is some genuine harm done — real or perceived — to an individual, by another. The harm may be physical, emotional, or spiritual, affecting any one of a host of important areas: our pride, our emotional or physical well-being, our finances, our security, our relationships, and many other areas. The harm must be substantial — the injury must cost us something dear, thereby engendering the inevitable responses to such harm: fear, pain, sorrow, loss, anger, resentment, disruption of relationships. The need for forgiveness arises out of these natural defensive responses to the offense — defenses which have an unnerving tendency to be self-perpetuating and self-destructive.

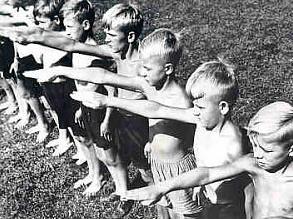

Some of the silliness surrounding the act of forgiveness arises from the lack of such substantial harm. Choosing, for example, to forgive the Nazis for the Holocaust, or the terrorists for 9/11, for example, when we ourselves have never been affected by it directly in any way (or at best trivially so), becomes little more than pretentious posturing. It costs us nothing to say, accomplishing nothing but the appearance of self-righteous sanctimony. This form seem especially common in some Christian circles, where it serves little more than a veneer of righteousness, allowing us to sound “Christian” while sacrificing nothing.

False forgiveness commonly takes another form, driven by obligation to moral or religious dictates, and facilitated by denial. Having sustained some harm, we know the moral command to forgive, and therefore simply will ourselves to do so. When the inevitable anger arises again — as it always will, if there has been substantial harm — we simply force it under the surface, recommitting ourselves to the act while trying desperately not to relive the incident. Yet the anger and resentment never get resolved, and arise repeatedly — often in areas of life far removed from the direct injury, manifesting themselves in depression, irritability, and acting out in other relationships or domains of life. The forgiveness driven by moral compulsion or law far more enslaves the giver than frees him, and allows the poison to fester rather than lancing the boil.

True forgiveness at its heart is about sacrifice. It is an extension of grace, a humble admission that we too have harmed others — perhaps even been instrumental in precipitating by our own behavior the offense we have sustained. It arises from a profound gratitude at having been forgiven ourselves, by God, of far greater failings than those which have wounded us.

Yet there is more to forgiveness than just having the the proper spirit — there must be action. Forgiveness arising from the right spirit is still frail — the emotions, the hurt, the resentment remain all to close at hand, as the injury is relived time and time again. The feelings persist though the spirit forgives. The heart must be transformed — it must, in fact, be dragged to victory by the will manifesting itself in changed behavior toward the offender.

Corrie ten Boom and her family secretly housed Jews in their home during WWII. Their “illegal” activity was discovered by the Nazis, and Corrie and her sister Betsie were sent to the German death camp at Ravensbruck. There Corrie would watch many, including her sister, die. After the war she returned to Germany to declare the grace of Christ:

It was 1947, and I’d come from Holland to defeated Germany with the message that God forgives. It was the truth that they needed most to hear in that bitter, bombed-out land, and I gave them my favorite mental picture. Maybe because the sea is never far from a Hollander’s mind, I liked to think that that’s where forgiven sins were thrown. When we confess our sins, I said, God casts them into the deepest ocean, gone forever. And even though I cannot find a Scripture for it, I believe God then places a sign out there that says, ˜NO FISHING ALLOWED”.

The solemn faces stared back at me, not quite daring to believe. And that’s when I saw him, working his way forward against the others. One moment I saw the overcoat and the brown hat; the next, a blue uniform and a cap with skull and crossbones. It came back with a rush — the huge room with its harsh overhead lights, the pathetic pile of dresses and shoes in the center of the floor, the shame of walking naked past this man. I could see my sister’s frail form ahead of me, ribs sharp beneath the parchment skin. Betsie, how thin you were! That place was Ravensbruck, and the man who was making his way forward had been a guard — one of the most cruel guards.

Now he was in front of me, hand thrust out: “Fine message, Fraulein! How good it is to know that, as you say, all our sins are at the bottom of the sea!” And I, who had spoken so glibly of forgiveness, fumbled in my pocketbook rather than take that hand. He would not remember me, of course! How could he remember one prisoner among those thousands of women? But I remembered him. I was face-to-face with one of my captors and my blood seemed to freeze.

“You mentioned Ravensbruck in your talk”, he was saying. “I was a guard there.” No, he did not remember me. But since that time, he went on, “I have become a Christian. I know that God has forgiven me for the cruel things I did there, but I would like to hear it from your lips as well, Fraulein” — again the hand came out — “Will you forgive me?”

And I stood there — I whose sins had again and again to be forgiven — and could not forgive. Betsie had died in that place. Could he erase her slow terrible death simply for the asking? It could have been many seconds that he stood there — hand held out — but to me it seemed hours as I wrestled with the most difficult thing I had ever had to do.

For I had to do it — I knew that. The message that God forgives has a prior condition: that we forgive those who have injured us. “If you do not forgive men their trespasses,” Jesus says, “neither will your Father in heaven forgive your trespasses.” And still I stood there with the coldness clutching my heart.

But forgiveness is not an emotion — I knew that too. Forgiveness is an act of the will, and the will can function regardless of the temperature of the heart. “Jesus, help me!” I prayed silently. “I can lift my hand. I can do that much. You supply the feeling.” And so woodenly, mechanically, I thrust out my hand into the one stretched out to me. And as I did, an incredible thing took place. The current started in my shoulder, raced down my arm, sprang into our joined hands. And then this healing warmth seemed to flood my whole being, bringing tears to my eyes.

“I forgive you, brother!” I cried. “With all my heart!” For a long moment we grasped each other’s hands, the former guard and the former prisoner. I had never known God’s love so intensely, as I did then. But even then, I realized it was not my love. I had tried, and did not have the power. It was the power of the Holy Spirit.

To experience the miracle of forgiveness, we must relinquish our right to revenge, to serve justice on our enemies — for justice served in retribution is a toxic victory, shallow in satisfaction, engendering only hatred and bitterness and slavery. To be free, we must act: to make amends to those who have hurt us, when we have played a role; to pray for those whom we resent; to reach out and serve, if by pure will alone, to those whom we hate, that such hate may be transformed into transformational love. In this manner alone may we experience the deep miracle and healing that is true forgiveness.

In my previous post on guilt and shame, I discussed their nature and differences, their impact on personal and social life, and their instrumentality in much of our individual unhappiness and communal dysfunction. If indeed shame is the common thread of the human condition–fraught as it is with pain, suffering, and evil–it must be mastered and overcome if we are to bring a measure of joy to life and peace to our spirits and our social interactions.

In my previous post on guilt and shame, I discussed their nature and differences, their impact on personal and social life, and their instrumentality in much of our individual unhappiness and communal dysfunction. If indeed shame is the common thread of the human condition–fraught as it is with pain, suffering, and evil–it must be mastered and overcome if we are to bring a measure of joy to life and peace to our spirits and our social interactions. A wise friend–a man who helped me emerge from a period of considerable difficulty in my life–once taught me a simple lesson. In less than a minute, he handed me a gift which I have spent years only beginning to understand, integrating it into my life with agonizing slowness. It is a lesson which intellect cannot grasp or resolve, which faith only begins to illuminate–a simple principle which I believe lies close to the root of the human condition.

A wise friend–a man who helped me emerge from a period of considerable difficulty in my life–once taught me a simple lesson. In less than a minute, he handed me a gift which I have spent years only beginning to understand, integrating it into my life with agonizing slowness. It is a lesson which intellect cannot grasp or resolve, which faith only begins to illuminate–a simple principle which I believe lies close to the root of the human condition. David Brooks, in his NY Times Op-Ed piece,

David Brooks, in his NY Times Op-Ed piece,

Roger L. Simon recently had an epiphany. While reporting from the Durban II conference, he encountered the face of evil: President Ahmadinejad of Iran. He describes this encounter thus:

Roger L. Simon recently had an epiphany. While reporting from the Durban II conference, he encountered the face of evil: President Ahmadinejad of Iran. He describes this encounter thus: