Revenge of the Fifth

It seemed like such a great idea at the time…

His name is Darin. Of course, that’s not his real name, but he is a casual friend of mine. A bright young man, possessed of good looks, a warm smile, and a soft-spoken demeanor. Darin is brilliant with computers–not merely competent, as many are, but a true geek, tear-’em-down-and-rebuild-’em smart, fearless in the depths of sockets and motherboards, Windows registries and Unix terminals. A true success story, you might say, bright future, make some girl very happy. But Darin was toolin’ down the freeway of goin’ nowhere fast.

It seemed like such a great idea at the time…

His name is Darin. Of course, that’s not his real name, but he is a casual friend of mine. A bright young man, possessed of good looks, a warm smile, and a soft-spoken demeanor. Darin is brilliant with computers–not merely competent, as many are, but a true geek, tear-’em-down-and-rebuild-’em smart, fearless in the depths of sockets and motherboards, Windows registries and Unix terminals. A true success story, you might say, bright future, make some girl very happy. But Darin was toolin’ down the freeway of goin’ nowhere fast.

You see, Darin had a little problem: a fondness for the grape and the snort which always seemed to get the best of him. Not that he didn’t try: he was in and out of AA rooms more often than a pastor’s wife at church socials, always returning beaten and remorseful, determined to do better this time. “This time” rarely lasted more than a few weeks or months.

Darin was quiet, but a man of passion. He was always in love. Intoxicated with the flush of a new romance, that rush of euphoria so real yet so maddeningly transient. Each new girl was “the one”, but nights of passionate, drug-enhanced sex soon proved impotent to overcome the waning charms of Miss Demeanor, the rumpled sheets, and the rumblings of his restless soul. Before long he was again cruising for some other codependent wench, herself seeking a sodden soul to save. Like an ugly tie wrapped up pretty under the Christmas tree, Darin’s package looked good at first glance, but he quickly proved to be a daddy’s nightmare: “no phone, no food, no rent”, as the song goes. Soon he was once again welcome only in his mother’s house, with whom he could do no wrong.

Unfortunately, the same could not be said of Darin: someone did him dirty, stiffing him out of a good deal of cash, and forgiveness was not one of his many charms. The details are murky: a computer built or repaired, promises made but not kept. There was much lighthearted chatter at the coffee houses–was it Darin’s fault, or his nemesis? No matter–like a quiet bubbling cauldron in a witch’s lair, Darin was cooking up his favorite dish: a rip-roaring resentment. Not visible on the outside, of course, but raging like a Jerry Springer slug-fest in the conference rooms of his mind. It was the perfect mixed drink: a perceived injustice blended with that unique obsessiveness which addicts possess seemingly in endless measure.

It is not clear when the brainstorm struck–an idea so brilliant, so flawless, that it would right all injustices and settle all disputes: Darin would break into his detractor’s home and steal back the computer which tortured him so. No mere larceny, mind you, but the picture-perfect crime, a liberation to rival Paris in ’45. Carefully timed when the enemy was not at home, staged so not even Sherlock Holmes would presume that Darin might be the perpetrator. Sweet revenge, sweetly executed.

Like tightly-written computer code, Darin’s nimble mind set the parameters, checked the variables, and executed commands in a tight loop whose efficiency and speed wasted no cycles. The Day of Vengeance arrived, with only one small ingredient missing: courage. But Darin had that algorithm factored as well: a fifth of Vodka erased all fears, drowning all doubts. By stealth of night, with watches synchronized and bottle drained, the window glass parted to usher him to glory. The mission was underway.

No one knows whether anyone heard the shattering of glass, but despite his stealth the disruption somehow caught the notice of neighbors. When the police arrived, the cause of the disturbance became evident: there was Darin, passed out on the floor, beside the untouched computer he coveted. Fate had struck a cruel blow–his celebratory blackout had arrived on the wings of Mercury rather than with the spoils of Mars. He awakened to handcuffs and an open-ended reservation at the Gray Bar Hotel.

All good stories–even true ones–should have a moral, but Darin’s story eludes easy lessons. He was taken by that peculiar insanity which alcoholics possess in abundance, even while sober. When Darin hatched his master plan, he was not drinking, but engaged in one of his countless attempts to clean up. For the alcoholic, the danger lies not in the bottle, but in the brain. The sane among us make mistakes, to be sure: wisdom comes from experience, and experience often comes from lack of wisdom. But facing the inevitable consequences of bad choices, we generally rearrange our lives and priorities to ensure that such a travesty does not happen again. Not so the alcoholic. Obsessively repeating behavior long ago proven destructive, he nevertheless pursues the optimism of denial which says the next time will be different. This baffling disconnect from reality cascades from farce to tragedy, as the alcoholic perceives no problems other than those bastards who are out to get him.

There is much resistance to the idea that alcoholism and addiction are a disease. Much of this comes from conservatives, and those of religious conviction, whose proper emphasis on personal responsibility and moral rectitude sees in the alcoholic only reckless hedonism and wanton irresponsibility. These qualities the addict has in spades, but less obvious is the driving obsessive compulsion, the thought disorder which is their engine. The medical evidence for the disease model of alcoholism and addiction is deep and wide, as I have detailed in part elsewhere (see also this and this for more on the topic). The liberals have this one right: the alcoholic is a victim of his or her genetics, and the addition of a mind-altering drug–which one is probably moot–starts a swirling whirlpool whose vortex holds only misery, destruction and death. Not many survive its power.

Yet defining deviance from normal as disease also has its risks: the proliferation of social disorders redefined as diseases seems endless, and points to the abrogation of all responsibility for one’s actions. It can become laughable at times.

Several years ago, I saw a patient, a healthy, athletic women in her 40’s, who was covered under Medicare. Medicare covers the elderly, but also those with chronic renal failure and the disabled, so I inquired as to the nature of her disability. I was informed she had “hyperactivity disorder.” Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)? No, just hyperactivity disorder–she was restless. A black belt in Karate, she traveled around the country constantly, competing in tournaments and teaching seminars. She was disabled, in short, because she couldn’t sit still. No “cripple” jokes around her, no siree, unless you wanted your skull crushed by a foot you’ll never see coming.

The concern about labeling alcoholism, or any other behavioral disorder, as a disease is the tendency to tolerate and rationalize the resulting behavior, to use the “disease” label as an excuse for selfish, self-centered behavior destructive to one’s self, society, and those around you. The issue is not disease or no disease, but rather what drives the behavior and what can be done to change it. The paradox about 12-step programs–which have the only reliable track record for successful recovery from addiction–is that they emphasize the disease as the problem, and honesty, integrity, and personal responsibility as the solution. They do not excuse the behavior while admitting the disease, and this blend of honesty and humility, acceptance and tough love, works like nothing else. It is, as recovering alcoholics are quick to point out, a spiritual program: the Catch-22 of a body which craves alcohol without limit and a mind which denies the resulting problems cannot be solved any other means.

But as any recovering alcoholic will tell you, the problem is not the booze; it is not even the obsessive, irrational mindset which drives the drinking. Both these problems are symptoms of an underlying decay, one of spiritual dimensions, characterized at its core by extreme self-centeredness. The pursuit of happiness by feeding this monster creates not the promised joy but rather pain and emptiness. Alcohol hides that pain for a while, until the monster, growing ever stronger by its constant feeding, kills its host spiritually, emotionally, and often physically.

But addiction is hardly alone as a symptom of this dark core. The list of destructive behaviors arising from its belly is endless: obesity, sexual promiscuity, compulsive overwork, materialism, computer obsession, gambling, the pursuit of beauty over character, the lust for money and power. Some may be biologically-driven; some learned behaviors or dysfunctional coping. All seek to fill a hole with no bottom, providing the wrong salve for the pain, and more of the same when the salve makes the wound fester.

And what of Darin? In many ways he is fortunate: his life is on hold, and forced reflection and change are his for the taking–should he choose to grasp them. The price is high; it might have been much higher. Yet his choice–and ours–is the same: feed the monster, or turn life over to One whose burden is light, who alone can fill that deep inner void.

The war rages on. It is a battle with ancient roots, deeply embedded in religion, culture, and the tensions between rich and poor. It is a war of contrasts: high technology and primitive cultural weapons; knowledge versus ignorance; speed and urgency against the methodical slowness of an enemy who knows time is on his side.

The war rages on. It is a battle with ancient roots, deeply embedded in religion, culture, and the tensions between rich and poor. It is a war of contrasts: high technology and primitive cultural weapons; knowledge versus ignorance; speed and urgency against the methodical slowness of an enemy who knows time is on his side.

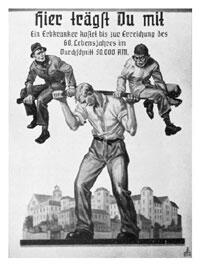

In the years following the Great War, a sense of doom and panic settled over Germany. Long concerned about a declining birth rate, the country faced the loss of 2 million of its fine young men in the war, the crushing burden of an economy devastated by war and the Great Depression, further compounded by the economic body blow of reparations and the loss of the German colonies imposed by the Treaty of Versailles. Many worried that the Nordic race itself was threatened with extinction.

In the years following the Great War, a sense of doom and panic settled over Germany. Long concerned about a declining birth rate, the country faced the loss of 2 million of its fine young men in the war, the crushing burden of an economy devastated by war and the Great Depression, further compounded by the economic body blow of reparations and the loss of the German colonies imposed by the Treaty of Versailles. Many worried that the Nordic race itself was threatened with extinction.

In contemporary political discourse, we often discuss the Rule of Law, especially in our postmodern culture where bad behavior is often justified (and excused) by situation, upbringing, or historical injustice. But no one ever talks about the Law of Rules.

In contemporary political discourse, we often discuss the Rule of Law, especially in our postmodern culture where bad behavior is often justified (and excused) by situation, upbringing, or historical injustice. But no one ever talks about the Law of Rules.