An ongoing study of the epistle 1 Peter.

- Letter from an Apostle – Background

- 1:1 — This letter is from Peter, an apostle of Jesus Christ. I am writing to God’s chosen people who are living as foreigners in the lands of Pontus, Galatia, Cappadocia, the province of Asia, and Bithynia.

The apostle Peter, one of the 12 apostles of Jesus, appears frequently throughout the Gospels and the book of Acts. He was a fisherman, chosen by Jesus, and one of the inner circle of the disciples. He was present at the transfiguration of Jesus; in the garden of Gethsemane; at his trial, where he denied Jesus; and was appointed by Jesus to lead his Church. By declaring himself an apostle (apostolos)– a specific claim to have been appointed directly by Christ to teach and lead His Church — Peter is declaring his authority to speak on behalf of Christ Himself.

He addresses his epistle to those “chosen” of God and “foreigners”, in areas located in modern-day Turkey. The imagery here is strikingly similar to that used of the Jewish people, who also were spoken of God’s chosen people, many of whom represented a diaspora spread throughout the ancient world.

We do not know if Peter was writing to these churches which he himself had founded, or to Christians whom he had evangelized, or whether he was speaking to those he had never met, in his office as the chief of the apostles. He does not mention specific individuals — unlike many of Paul’s letters — which may suggest he himself had not founded these churches.

The use of the term “foreigners” (or “sojourners” or “pilgrims”) speaks to those who are not natives in the land in which they dwell. This suggests that these were either converted Jews of the Diaspora (for Peter was the apostle to the Jews), or perhaps Gentile Christians who had emigrated to Asia minor. As Peter will develop later in the epistle, however, there is also a sense of the Christian in the world as a pilgrim: a foreigner traveling to a world not his own, while a citizen of heaven.

- 1:2a — God the Father knew you and chose you long ago…

“God the Father…”

This is shockingly and intensely personal. It is not God the Creator; God the lawgiver; God of judgment; God unapproachable, inscrutable, unknown. This is family: this God, although vastly above us and beyond our understanding, nevertheless considers us children, family, friends. This is a stunning contrast to the religions of this and every age, with gods either mythical, or vengeful, or distant and impersonal. This is a God of profound love, of tenderness, of mercy, of gentleness; a teacher, a guardian, a guide, a defender. Even among the Jews, who worshiped and served the same God, there was no sense of such intimate personality; theirs was the Yahweh of Sinai and the burning bush, a God to be feared and obeyed but surely not befriended. The God whom Peter came to know through Jesus Christ was an utterly new revelation, a profound paradigm shift in man’s understanding of God.

“God the Father knew you…”

We are known: intimately, throughout eternity, in every moment and every aspect of our lives. This is not mere familiarity, nor faint acquaintance: this is full, complete, transparent knowledge, that of the Creator fully comprehending His own creation.

We are known: in all our greed and selfishness; in our gossip and backstabbing; in our anger, and deceit, and hatred, and arrogance. The God of eternity, transcending time, knows our every moment, our every thought, our every action, our birth and death and all that lies between. “Every hair on your head is counted” — there is naught that is hidden, every corner of your soul, every cell of your body is known by God, throughout eternity.

We are known: not only in our deep rebellion and sinfulness, but in the glory which we might bring Him, and His purposes which we may serve. We are known in our fullest and highest potential; the goodness which God can bring about when we are once again restored to Him, empowered by Him, guided and gifted through Him. In this too we are known.

We are creatures of time; we have a beginning, and an end, and the sequence of minutes, hours, and days which pass between, one after another. Yet the God who knows us is above and outside time; He is eternal, unbounded by that which He has created. Every moment of our lives is now for God; He inhabits our past, our future, our eternity with Him yet to come: these are present to Him, who transcends time and redeems it.

“God the Father knew you and chose you…”

To be chosen: to be accepted in whole, unreservedly, unconditionally. This is the very deepest need of man; our rejection by God and man fosters an endless parade of human misery, suffering, pathos and pathology. Our entire lives are spent seeking the acceptance of others, and failing to find in them the acceptance which is our very life. Deep within each of us dwells a bottomless abyss, into which we pour an endless train of insufficient and destructive detritus. We seek to fill the abyss with material goods; with drugs, or alcohol, or food, or sex; we seek relationships, hoping through them to fill that void — then destroy those relationships when they fail to accomplish what they are utterly incapable of fulfilling. Neither power, nor money, nor eminence, nor the esteem of others will suffice. Only to be chosen by God; to be accepted, fully, unconditionally, eternally by Him: this alone fills the despondent destitution within — for that emptiness was made to be filled with naught but God Himself.

And we are chosen, not because we have earned this esteemed position; not because our behavior has made us worthy, nor our status gained God’s attention, nor our inflated self-worth merited his favor and mandated his choice. We are chosen: broken, failures, rebellious, arrogant, fully worthy of utter rejection — yet by grace, plucked from the mire of hopeless self-destruction and empty, purposeless lives, for the sole reason that we are loved, and that this love can transform us from something useless and empty to something purposeful and valued. We are chosen because we are loved, though unworthy, and because we may become empowered by our choosing to manifest that same love to a lost, desperate world.

We were chosen long ago — as we measure time.

Yet the time of our choosing is now, if we will but accept it.

The recent arrest of Roman Polanski for statutory rape with a 13-year-old girl has peeled back the veil covering our cultural decay. Numerous artists, directors, and other Hollywood celebrities and powerbrokers have come out and condemned the arrest, while rationalizing his behavior and condemning what they see as unjust punishment. The public response to this has been somewhere between shock and revulsion, with many commentators, even the New York Times editorial page, expressing surprise and dismay at Hollywood’s response to a man who drugged and raped a minor.

The recent arrest of Roman Polanski for statutory rape with a 13-year-old girl has peeled back the veil covering our cultural decay. Numerous artists, directors, and other Hollywood celebrities and powerbrokers have come out and condemned the arrest, while rationalizing his behavior and condemning what they see as unjust punishment. The public response to this has been somewhere between shock and revulsion, with many commentators, even the New York Times editorial page, expressing surprise and dismay at Hollywood’s response to a man who drugged and raped a minor. We struggled through some intimidating “God-words” — justification and sanctification — in my

We struggled through some intimidating “God-words” — justification and sanctification — in my  In my

In my

On an

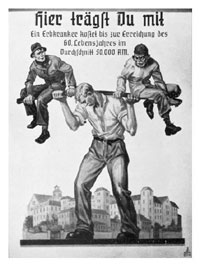

On an  In the years following the Great War, a sense of doom and panic settled over Germany. Long concerned about a declining birth rate, the country faced the loss of 2 million of its fine young men in the war, the crushing burden of an economy devastated by war and the Great Depression, further compounded by the economic body blow of reparations and the loss of the German colonies imposed by the Treaty of Versailles. Many worried that the Nordic race itself was threatened with extinction.

In the years following the Great War, a sense of doom and panic settled over Germany. Long concerned about a declining birth rate, the country faced the loss of 2 million of its fine young men in the war, the crushing burden of an economy devastated by war and the Great Depression, further compounded by the economic body blow of reparations and the loss of the German colonies imposed by the Treaty of Versailles. Many worried that the Nordic race itself was threatened with extinction.