Dr Bob

Justification, Sanctification, and Grace

If you’re browsing along, and see the topic of this post, chances are good you’ve already clicked the next link on your blogroll, especially if you’re not a Christian. You probably don’t realize this isn’t really a theological discourse — well, in a way it is, I suppose, as all discussions of the spiritual life are in some way theological — but my intent is not to bore you to tears. But I will certainly understand if you can’t get past the “God-words.” No problem, happy browsing, drop back again for another topic of more interest to you.

If you’re browsing along, and see the topic of this post, chances are good you’ve already clicked the next link on your blogroll, especially if you’re not a Christian. You probably don’t realize this isn’t really a theological discourse — well, in a way it is, I suppose, as all discussions of the spiritual life are in some way theological — but my intent is not to bore you to tears. But I will certainly understand if you can’t get past the “God-words.” No problem, happy browsing, drop back again for another topic of more interest to you.

Even if you are a Christian, you’re probably getting a little nervous already, as your eyes glaze over when this sort of stuff gets talked about at church or your bible study. Hang with me a few minutes, then surf on if I get too deep — fair enough?

Good, glad you stayed.

In a prior post on purpose in life, prompted by some musings by Rick over at Brutally Honest (no longer an active blog), we got some discussion going — at both blogs — on these very topics. Yes, we all need a life, I suppose — unless this stuff really is about getting a life, at least one that matters. At the core of this discussion is some reflection on how well we’re doing in life — specifically whether our lives make a difference to someone other than ourselves, whether as Christians (or just people trying to do the right thing) we’re behaving in ways which are pleasing to God, or meet with His approval, or following the Golden Rule — whatever that might be.

I recall a conversation I had some years ago with a young man in Britain, in the old Compuserve forum days. He, an atheist/agnostic, said something to the effect of, “All religions are the same — there’s basically a set of rules to follow, and if you obey them, you get rewarded by going to heaven.”

And I agreed with him (to his surprise) — with one caveat: that Christianity is the one exception to his otherwise astute observation. In Christianity, it’s not about doing something different, it’s about becoming someone different.

So how does that work? And aren’t Christians all about being good, following the Bible, going to church — and condemning and judging those who don’t?

Yeah, all too often we are. Sad but true. But that’s not really how it’s supposed to work, you know. Which is how we somehow started discussing these “God-words,” or what I call the “-cation” words: justification, sanctification, and vacation. (Well maybe not the last one, but God do I love vacations!). So what do they mean?

Well, “justification” is really a legal term — same root meaning as justice. The term was used in ancient Greek civic culture for writing off a substantial, unpayable debt. It basically says we’re seriously busted, in deep doo-doo, goin’ to court before the judge with a public defender who was out drinking all night and comes to court with a bimbo on each arm. We’re guilty as sin, our tattooed arms and body piercings are on full display, and sitting on the throne is Judge Judy — and she’s got her bitch on, bad. We’re goin’ up the river for a life of TVs in our cells and tin cups, weight rooms and a big guy named Willie who thinks we’re really, really cute.

Then this dude whispers in Judy’s ear. She grumbles a bit, huffs, then blows us away with some unexpected news: you’re free to go. Your guilty as charged, but some stranger has stepped in and offered to do your time for you, to pay your debt in full. Whaa???? Dude!! “As far as this court is concerned, you are as good as innocent”, says the Judge. “Now get outta here!”

That’s justification.

Declared “not guilty” through no merit of my own. Too good to be true. Why would anyone do such a thing?

Well, to push the metaphor, already strained, a bit farther: it seems this guy who’s paid the price to set you free has been watching you for a long, long time. He’s sees in you something of himself, and envisions for you a potential far greater than anything you could ever imagine. He’s got great plans for you; you fit just perfectly into a grand scheme he’s been thinking about since long before your sorry ass landed on this planet. It’s worth it to him to pay such a price, because the outcome of this grand plan means everything to him. And so he’s given you this gift to make it happen. For free.

Well, there is just one small detail I forgot to mention: a small “postage and handling” fee for this get-out-of-jail transaction. This little liberation will cost you, ummh, pretty much everything you now value. Your self-will. Your selfish, self-centered pig-headedness. Your arrogant and clueless idea of what’s best for you and what will make you happy. Your crazy idea that if you do what you want and get what you want, you’ll finally be content and at peace (how’s that workin’ out for ya?). In other words, all that garbage which got your sorry butt busted in the first place.

Bend the knee, suckah — instead of serving time, you gonna be serving eternity.

Suddenly the deal’s not lookin’ so good. You’ve heard Willie’s not such a bad guy after all — and you have been meaning to get pumped up and work on that 6-pack you’ve always wanted…

But in the end you decide to trust this crazy guy whose already footed the bill for your get-out-of-jail-free card. Of course, he already knows what a pathetic sonofabitch you are, and having spent the big bucks to get you off the hook, is fully prepared to do the heavy lifting necessary to transform you into the useful and happy partner — dare I say friend? — which he’s always envisioned you to be. But first you need a major cleanup, starting from the inside out, since a whitewash is never gonna cut it. Extreme makeover needed — on the inside. The outside will take care of itself, in time.

This, my friends, is what we call sanctification.

An extreme makeover–from the inside out. Sounds, painful…

It is–and also, impossible. Especially if we try to do it ourselves.

Having won the lotto and walked out of court with no prison rap, you are, understandably, pretty darn grateful to this mysterious benefactor whose been so incredibly generous and kind to you. So, of course, not quite getting the program, you try to follow the rules he seems to have in place, figuring this will make him happy. So you go to church; start reading the Bible; say a few prayers; try to be good. You hang around with others who been similarly pardoned — although you find them pretty darn boring, compared to the run-and-gun crowd you’ve always hung out with.

And it really doesn’t work out all that well. The harder you try, the more you come up short. The siren song of your life of self-service is always singing in your ears, beckoning you back to that “happy” life and the “good times” you remember. You fall on your face — a lot. And those Christian “friends” you have? They’re starting to really get on your nerves. Telling you to just try harder, pray more, read your Bible (like that works!). Frowning a lot when you share with them your weaknesses and failures. Talking about you behind your back because you’re a “backslider.”

The demons inside start running the show more and more, those addictions and obsessions which you were supposed to get rid of when you signed on to this deal. They start sounding ever more reasonable, comforting you with how important it is to get your needs met. Before you know it, you are making a bee-line toward the place where you began — or worse. Those seductive voices even begin to sound a lot like God, so surely you must be on track, and with some more effort you’ll surely get there. You wonder where this “peace” and “happiness” is they sing about and talk about in church — and to be honest, those hypocritical holier-than-thou Christians don’t look all that happy and joyful themselves — bastards. Pretty soon it all seems like a bad dream, and you’ve ended up worse off than you began.

This, my friends, is not sanctification. This is slavery.

You’re trying to build the perfect house with defective tools and flawed materials. You’re using your very best efforts to improve your lot when your very best efforts are your very worst enemy. You’re trying to perform that extreme makeover, working from the outside in. The outside may look a little better — but the inside is still the same: selfish, self-centered, fearful, ugly, dark. You are trying do the work of God with the hands of man — and you are doomed to fail. You end up exhausted and spent, and never become that integral and integrated person who makes God’s purposes move forward and makes your own life meaningful, contented, and filled with the satisfaction of living with purpose.

I know. I’ve tried this approach. Didn’t work out so well.

So how is it supposed to work, this Christianity thing? Are we set free only to spend the rest of our lives as miserable failures scrambling to meet a host of impossible goals? The answer, as you might expect, is no. The key is a truly strange and rather wonderful solution indeed. It is far more strange — bizarre even — than anything you might have imagined.

It is a thing called grace.

And like any good daytime soap or episode of Project Runway, I will leave you wondering just what that funny word is all about … until my next post, anyway.

Thanks for sticking with me. Back soon with more.

On Purpose

Rick over at Brutally Honest hooked me with a post on, of all things, zombies:

I question consistently whether I’m living a worthy life. Hence the reference to that ending scene where Private Ryan, now an old man kneeling at the grave of the Captain who saved his life, turns to his wife and pleads “Tell me I have led a good life. Tell me I’m a good man.” … Indeed, I find [the question of whether am a walking dead man] terrifying. Perhaps it’s my Catholic upbringing with its focus on guilt. Perhaps it’s my exposure later in life to evangelical Christianity and it’s focus on being saved. Or perhaps it’s simply something I focus on in case this whole notion of God’s mercy and grace, where I live and hope today, are in error.

Its funny how these things seem to drop in on you when you’re thrashing about mentally on the very same topic — one might almost think it was more than just coincidence.

At the heart of Rick’s post lies the question, “Does life — my life — have meaning?” This is one of those questions which never seems to go away, no matter how much we try to drown it out. We hear, day after day, about how we are cosmic accidents, amino acids and random chance tossed into the whirling blender of evolution to produce a highly sophisticated human Margarita. In such a world, ruled by the cruel logic of cosmic chance, questions of meaning and purpose would appear frivolous and irrational. But nevertheless, they just keep popping up, like moles in the movie Caddy Shack. Even the fundamentalist secularists, the Dawsons and Hawkins and Hitchens of the world, can’t seem to tear themselves away from the language of purpose and intent, as they speculate how random chance and natural selection “choose” to create us and “select” the “best” genetic mishaps to produce that animal which we call man.

Ask your average man on the street what his or her purpose in life is, and expect in response some snide comment, humorous retort, or — if they be halfway serious — something approaching a short-term goal. So their “purpose” might be to graduate from school, or pass their exams, or become an attorney, or get laid this weekend, or get a better job. But in fact, such responses reflect in their commonality a profound shallowness so typical of an age where we have everything but that for which our hollow hearts hunger.

For it seems we often confuse goals with the idea of purpose. For the concept of purpose or meaning in life presupposes something beyond ourselves. It implies that we are fitting into a larger picture, a grander scheme, some overarching game plan vaster than ourselves, yet capable of including us in the fullness of its accomplishment. The idea of purpose does not necessarily mandate believe in a deity — although it leads quite naturally in this direction.

Inherent in the idea of purpose is an innate sense that we are aligned in some way with a greater good, a larger existence than that which we may measure and perceive. It implies simply that we are not merely one small cog in a complex machine, but rather an integral part, even an indispensable one, without which the machine can not fully accomplish that for which it exists.

If we confuse our goals with our purpose, we will inevitably end up frustrated and unhappy. If your goal is to graduate from college, when you graduate, do you now have purpose? Hardly. Instead such accomplishments merely mark a signpost, an indicator pointing to yet another goal, larger and even farther out of reach. Having arrived at our destination, we immediately set out towards a new goal — be it becoming a professional, or a carpenter, or getting married, or making a boatload of money. By simply resetting our goals into the future we believe — or want to believe — that we are moving forward with purpose. But once these newer goals are reached — or equally so if we failed to reach them — there is an inevitable emptiness, a sense of, “Is this all there is to life?” When you are finally successful in that career you have been working toward for decades, why is it that you find yourself so unsatisfied with arriving at this long-sought destination? If your goal is raising children, what will you do when they grow up and leave the house? You have met your goals, but have yet to meet your purpose.

The result is too often seen: the divorce, the new marriage, the philandering, the drinking, the obsessive pursuit of money and prestige and power, and an unholy host of behaviors which are far more destructive than satisfying. Such may serve in the near term to fill the emptiness which comes when goals are substituted for purpose, but they do not fill that inner need for being part of the greater good and accomplishing something of lasting value in life.

In my own feeble experience, having made a myriad of such mistakes myself, I have, I believe, finally stumbled upon the paradox of purpose: I know that I have a purpose in life — and I don’t know exactly what that purpose is. Nor, I suspect, will I ever know it fully this side of the undertaker’s icy slab. This is life in the realm of faith: that mysterious, almost intangible sense that you are on the right road, while being able to see neither your feet on the ground nor the path along which you’re headed.

So for now, my purpose is to serve those who have been put into my life as family, friends, and patients. I fulfill my purpose by being the best physician possible for my patients; by being a good husband and father; by being a loyal friend. It should go without saying that I meet these lofty ideals imperfectly and often poorly. But this is the standard against which I measure my conformity to purpose, a small shaft of light which casts just enough illumination to see where my next step should be.

Yet it is also apparent that my current striving to achieve such high ideals does not encompass a life purpose in its entirety. If I am a good physician, a good father, a loving husband, a loyal friend, I am following my life’s purpose as best I can discern. Yet if my purpose is comprised solely of being, say, a good physician, what then will my purpose be tomorrow should I be injured or incapacitated such that I can no longer practice my profession? My life may change enormously — yet my purpose will not. I will still have an ultimate purpose in life, but the vehicle through which I fulfill that purpose may change radically and wrenchingly, with agonizing violence.

It is here that I must rest almost entirely on the idea of grace — that there is a hand guiding me which does know the path and the purpose, and may in an instant radically change the rules of the game in order to more fully implement that larger purpose. To live in such a mindset requires a confidence in the existence and unfailing goodness of God — even while doubting that very existence and goodness more often than I care to share. Without grace, I am left to the ruthless serendipity of slavery: I am constantly wondering whether I am living up to a standard, or whether God is punishing me because of this change in course, or perhaps simply being capricious or vindictive for some past behavior. If my God is immutably good and gracious, my life’s purpose is will thereby be good by design — and will be — hard as it is to swallow — nearly invisible to my blinkered eyes.

To have purpose in life is to have confidence in the goodness of God, and a willingness to follow and trust in places I do not wish to go. To salve the fear inherent in such an unknown trust there comes a measure of inner peace that arises not from understanding, but from trusting. For is only when we walk by faith, not by sight, that our lives can truly begin to have that transcendent purpose which is the only worthwhile goal.

CAT Scams

The Wall Street Journal reports on a recent New England Journal of Medicine study which concludes that doctors are over-utilizing CT scans, exposing their patients to excessive, and potentially harmful, radiation doses:

The Wall Street Journal reports on a recent New England Journal of Medicine study which concludes that doctors are over-utilizing CT scans, exposing their patients to excessive, and potentially harmful, radiation doses:

Doctors are ordering too many unnecessary diagnostic CT scans, exposing their patients to potentially dangerous levels of radiation that could increase their risk of cancer, according to Columbia University researchers.

The researchers, writing in this week’s New England Journal of Medicine, conclude that in the coming decades up to 2% of all cancers in the United States may be caused by radiation from computed tomography scans performed now. Children face the most danger, they said.

In ordering CT scans, doctors are underestimating the radiation danger … In many cases, the researchers say, older technologies like X-rays and ultrasound that expose patients to lower radiation doses or no radiation at all would work just as well.

Since CT scans were introduced in the 1970s, their use has grown to an estimated 62 million annually. An estimated four million to five million scans are ordered for children, Mr. Brenner said. Adults receive scans for diseases of the stomach, colon, breast and other areas. Children most often are scanned for appendicitis. It has become a favored technology because it provides detailed information about patients’ bodies, is noninvasive and typically is covered by health insurance.

While the scans save lives, the authors say, doctors are leaning on them over safer diagnostic tools because they underestimate the levels of radiation people receive from the scans.

The authors measured typical levels of radiation that CT scans emit. They found levels they say were comparable to that received by some people miles from the epicenters of the 1945 atomic blasts over Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Japan.

There can be little doubt that CAT scans, as well as other expensive medical imaging studies, are overutilized in medicine today. There is also no doubt that the overutilization of CAT scans in particular, with their ionizing radiation, does expose patients to significantly more radiation. It may be worthwhile to pause and think about why so many CAT scans are being performed.

Hint: It’s not because doctors don’t know that CAT scans deliver more radiation.

Continue reading “CAT Scams”

Mortal Canyons

The wind whipped down the side street, as it does so often this time of year in New York. Like some entrapped banshee, it screeched, wildly, tearing past the long sharpened shadows of the afternoon sun, then suddenly, more restrained, whistling softly like a frightened child in a graveyard.

The wind whipped down the side street, as it does so often this time of year in New York. Like some entrapped banshee, it screeched, wildly, tearing past the long sharpened shadows of the afternoon sun, then suddenly, more restrained, whistling softly like a frightened child in a graveyard.

It burst forth upon the broad avenue, now swirling in whorls of unseen turbulence, sweeping up gently with hidden hands the week-old newspaper, tossing it in graceful arcs and dives like some savage cat toying with its prey, ending its flight with bored indifference in a doorway swinging gently in the lingering eddies. Its newsprint preached in foreboding tones of warming planet and warring sects, of homeless and health care and dishonest pols. But the world thus depicted was now convulsively changed, new beyond recognition, dark beyond comprehension.

Down the grand avenue, the lucent cadence of stoplights kept their ordered rhythm, now green, green-red, now red again, an endless choreographed chronos now futile in purpose, whose lifeblood yet poured forth through subterranean copper veins from whirling turbines crafted to run unattended, for days.

The synchronized lines of green and red receded unbroken, their vortex co-mingling at the vanishing point of the now-empty boulevard. The once-vibrant canyon stood lifeless, the once-seething froth of trucks and horns, cabs and transport now a dry wash devoid of motion, the scattered gravel of abandoned cars marking its course like tombstones on a high mountain pass. In funereal silence, a man lay slumped near a steam vent, its wispy vapors rising like a fugacious ghost fleeing some ghastly tomb.

Continue reading “Mortal Canyons”

On Miracles: Ancient Texts

Fourth in an ongoing series on the problem of miracles, and evidence for the Resurrection:

♦ Why bother with this old collection of myths, the so-called “Scriptures,” when trying to show that miracles existed, and that there was a resurrection of Jesus?

There is evidence (which I’ve already covered) that Jesus was a historical figure, and this evidence also provides considerable information about the beliefs of early Christians in the deity of Christ and alludes to belief in His Resurrection. But the secular references don’t give a lot of detail about these beliefs or the evidence for them. This is not unexpected, as they had little use for details about a crucified prophet and his followers, other than understanding why they were such a nuisance. For these details we must go to the accounts of those who were actual followers and believers in Jesus.

♦ Surely you don’t believe this stuff was “inspired”? You’ll have a tough time selling me that “inspired” writings can be used as historical evidence.

Well, I do believe that these writings were inspired — a discussion for another time, perhaps. But the “inspiration” of the NT documents is utterly irrelevant to their value as historical documents.

♦ Historical documents? You must be kidding! This stuff was written hundreds of years after the events it purports to describe.

Sounds like someone hasn’t done their homework. Yes, there was a school of biblical scholarship in the nineteenth century, led by Rudolf Bultmann and other German theologians, which maintained a late date of writing, placing it well into the second century or later. Their skepticism influenced a number of other biblical scholars as well. But facts have a stubborn way of deflating bad theories. We now know with virtual certainty, based on more recent archaeological manuscript evidence, that the last Gospel, John, was written no later than 90 A.D., and the other three considerably earlier. Luke, who wrote both a Gospel and the book of Acts, was a companion of Paul and is widely recognized by scholars as a superb, highly reliable historian. Paul’s own letters date back to within 20 years after the death of Christ, and he quotes ancient creeds (such as 1st Corinthians 15) which were in circulation at the time of his conversion, a few years at most after the Gospel events.

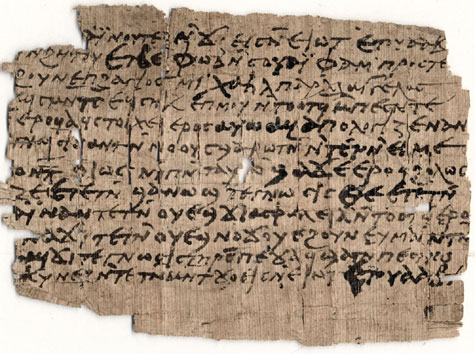

♦ Whatever. How reliable can a few old scraps of parchment be, anyway? Aren’t they all just copies of copies?

Well, pretty darn reliable, actually. Granted we have no “original signed copies” of the NT documents. But compared to most ancient literature, the NT is almost embarrassing in its quantity of source material and their temporal proximity to its events. Take Homer’s Iliad, the “bible” of the ancient Greeks, composed in 800 B.C. We have about 650 surviving manuscript copies from this work, the earliest ones dating from the second and third centuries, one thousand years after it was written. For Josephus, the first-century Jewish historian, we have nine manuscripts of his history of the Jewish War, copied in the ninth through eleventh centuries. Tacitus, the great Roman historian from early second century? Two manuscripts, the earliest in 850 A.D. Despite this paucity of source documents, scholars are quite comfortable that they accurately reflect the content of the originals.

How about the New Testament? Let’s see — over 5,500 Greek manuscripts and fragments, some dating to within one generation of the time of the Apostles. Another 20,000 or so exist in other languages. From the standpoint of source material for ancient literature, this is a rather preposterous prosperity.

♦ But they’re still just copies — lots of errors in that process are inevitable, to be sure.

Well, you underestimate the extreme care taken with copying such documents in the ancient world, especially those held in such high esteem as the NT scriptures. But some copying errors were inevitable, mostly transpositions and misspellings. The extraordinary number of extant copies allows an excellent cross-check, facilitating a high degree of precision about the content of earlier sources no longer available.

♦ OK, you’ve got some old documents which were written pretty close to the time of Christ. But there’s lots of other Gospels out there which disagree with those in the NT — why aren’t they considered good sources?

Good question. Yes, there’s a bunch of other writings which call themselves “Gospels” — The Gospel of Thomas (a favorite of the Jesus Seminar), The Gospel of Peter, the Gospel of Mary, the Gospel of Judas, and a number of other similar works. Much has been made of these by some, but they largely eliminate themselves as contenders through either their content, their date of writing, or both. First of all, unlike the NT Gospels, there is no evidence that they were authored by one of the Apostles or the Apostles’ companions. Secondly, most are dated rather late, in the 3rd and 4th century A.D. And lastly, their content is steeped in mysticism and Gnosticism, and borders on the bizarre in many cases. The Gospel of Thomas, for example, ends with a “saying” of Jesus which goes, “Let Mary go away from us, because women are not worthy of life. … Lo, I shall lead her in order to make her a male, so she too may become a living spirit.” Gloria Steinam, call your office.

♦ I’m glad you mentioned the Jesus Seminar — these biblical scholars determined that very little of what Jesus said and did in the Gospels is history, that most of it is myth. So much for your “Scholars believe the Gospels to be historical” argument, eh?

Well, most biblical scholars and archaeologists find the members of the Jesus Seminar to be an embarrassment, a fringe group with lots of media savvy but little scholarly credibility. The Jesus Seminar’s own stated goals were to ditch the traditional understanding of Scripture and create a “new fiction” and a “new Gospel.” In this they have clearly succeeded.

♦ Well, we all know that the Church simply decreed which books would be in the Bible, and invented its weird doctrines, like the Deity of Christ, the Trinity, the Virgin Birth, and the Resurrection. It was all a big power-play to keep control over the ignorant masses who mindlessly followed them.

Big fan of the The Da Vinci Code, aren’t you? Great writer, Dan Brown — lousy historian, too. The councils and synods merely affirmed what the Christian church had known to be true from its beginnings, and accepted and acknowledged those books already held to be genuine and apostolic in origin. The central doctrines which were supposedly “decreed” de novo by the councils are easily found in the writings of ancient church leaders and apologists — the so-called Church Fathers — several centuries before they were publicly affirmed in creeds and councils. It is child’s play to verify this yourself, as many excellent translations of these works are available — unless, of course, you’re not really interested in arriving at the right answer. Oh, and by the way: virtually every verse in the NT can be found cited in these early Christian writings — quoting from manuscripts no longer available. The NT really was written within a generation of the time of Christ, by eyewitnesses or their close associates, and was being cited by other authors within a few decades of their writing.

♦ But even if they’re early and reliable, these Scriptural sources are still religious, written by true believers, fanatics. Couldn’t they just say anything they wanted about Jesus, and expect their followers to buy it?

Well, sounds easy enough, but there’s a small problem: there were lots of folks who were itching to prove them liars. There were the Jewish religious leaders, first of all, who were definitely not amused at this heretical cult which had formed in their midst, preaching blasphemy. Peter stands up at Pentecost and tells a very large crowd of people, “Jesus of Nazareth was a man accredited by God to you by miracles, wonders and signs, which God did among you through him, as you yourselves know … God has raised this Jesus to life, and we are all witnesses of the fact.” So the Jewish leaders waltz over to the grave of Jesus, show folks the dead body, and Poof! The new cult goes belly-up in a heartbeat.

Then there’s the crowd he’s addressing, with quite a few folks who were around when Jesus was preaching, who witnessed his crucifixion, or who had at least heard about these events from other first-hand witnesses. Takes real chutzpah to stand in front of a large crowd and tell them something they (and you) know never happened. Peter could have made a lot of omelets with the eggs and tomatoes tossed his way if he tried that stunt.

♦ But you’re using circular reasoning — using a description of an event taken from a religious writing to prove that what it describes actually happened. What proof is there that this “sermon” by Peter in fact even happened, or that this is what he said?

Well, this description of Peter’s first sermon was written by Luke, in the book of Acts. Luke was a careful, detailed, OCD-kind-of historian. His narrative is filled with extraordinary details: detailed descriptions of maritime practices; ancient marketplaces and cultural customs; specific time and place references; names of secular and religious rulers. His stated intent was to seek out eyewitnesses to the events of which he wrote. He accompanied Paul on one of his missionary journeys, and traveled with him to Jerusalem where he had contact with Peter and the other Apostles. His writing depicts much that archeology and other historical sources verify, and contains nothing of the excesses and hyperbole common to legendary development.

Yes, Luke had a religious bias, as did all the NT writers, because of what he heard and saw from eyewitnesses. If his religious convictions alone exclude his writings as unreliable, then methinks the problem is with your preconditions and prejudices, rather than with the accuracy of Luke’s narrative.

♦ Well, everyone knows that whole empty tomb thing was just a grand hoax — the disciples stole the body, and then claimed a “resurrection” to make themselves religious big-shots.

Well, maybe everyone you know thinks that — but I wouldn’t bet your inheritance on it. But that discussion will have to wait until my next post. Stay tuned.

UPDATE: If you are interested in more depth on the reliability and veracity of the NT documents, I suggest this book (full text online) by NT scholar F.F. Bruce. There are many others, but this is easily digestible and short by one of the best scholars in the field.

Bad Advice, Goddess

Amy Alkon, the Advice Goddess takes on the unenviable task of defending Ann Coulter in her latest ill-spoken diatribe on Christians and Jews:

Now, if you’re a Christian, chances are, it’s because your parents were Christians, and they took you to church and told you you were one, too. Typically works the same way for Muslims, Jews, and the rest. Few people actually make a conscious decision to worship a certain religion, let alone consider whether any belief, sans evidence, in god, makes sense…yet people of each religion tell themselves, essentially, “We’re cool and everybody else sucks!” (Neener, neener, neener!)

Now the Goddess is one smart cookie, who’s more than capable of defending a contrarian position. And although Coulter’s raving critics ain’t exactly throwin’ heat on this topic, the Goddess nevertheless wiffs big-time on this one — and in fact makes the exact same mistake that Coulter’s interviewer made, along with many of her critics. Sorry to say, it’s back to the dugout for the Goddess.

Not that I want to step up to the plate to defend Ann Coulter — she’s a major contributor to the rabid attack school of political discourse, barely a hair’s breadth above the Michael Savages and Michael Moores of the world; all heat, no light, genuinely obnoxious. If I were king, duct tape would be firmly applied — with super glue — to all such flapping orifices. I know, freedom of speech and all, yada, yada, but a guy can dream, can’t he?

But back to the Goddess — her core rebuttal, if I read her correctly, is that all religions believe they have the truth, and so of course they believe the next guy’s religion doesn’t — or at least is less enlightened or “complete” than they are. So why be offended, after all? I prefer chocolate ice cream, you prefer vanilla, so chocolate is “better” than vanilla, no? True enough, as far as it goes — which really isn’t nearly far enough when talking about matters of faith and religion.

The assumption which the Goddess makes is exactly the assumption Coulter’s interviewer, and his kindred spirits in media and the secular intelligentsia make, to wit: religion is nothing more than a personal or cultural preference. You get raised a Catholic, you grow up Catholic, or Jewish, or Muslim, or whatever. The idea that one might be able to measure such things against an absolute standard of truth is anathema to this way of thinking. The default logic is, all religions claim to have the truth, about things which are unprovable, so let’s just dismiss them all as fantasies and move on, shall we? The Goddess tips her hand to this line of thinking when she says:

Obviously, if Coulter didn’t prefer Christianity to Judaism and other religions (or didn’t think it would sell books — like all the rest of her shock-jockery)…she wouldn’t be a Christian. I mean, is this really so hard to grasp? Is it offensive? Or is it just…her opinion? Just as it’s my opinion that this country and the world would be much better off if the silliness that is belief without evidence in god was wiped out tomorrow, and people started living rationally.

Ahh, the old “faith is belief without evidence” line — where have I heard that one before? Sigh. It’s sad to see bright people fall face-down into this kind of intellectual porridge (not too hot, not too cold), this mental miasma whose sweet aroma is seductive but deadly to true philosophical integrity. A nice, easy comfortable generalization, this — salving the spirit while deadening the soul.

Now, don’t get me wrong: there’s lots of religions out there on pretty thin ice when it comes to providing solid evidence that their beliefs are at least reasonable. If you’re a Mormon, for example, you need to get past Joseph Smith’s scams and skills as a con-man, well-documented by a (former) Mormon historian, as well as the absolute dearth of archaeological evidence for the battles and civilizations depicted in the Book of Mormon. If you’re a Scientologist or New Ager, well, abandon all hope of finding objective evidence supporting belief in these religions which revolve in the far outer orbits of reality. In fact, when you get to the heart of most religions, there is a large central core of belief which cannot be objectively substantiated, whether it be reincarnation, or ancestor worship, or animism, or pantheism, or the fevered prophetic mutterings of Mohammad.

Then you come to Christianity.

And that sucking sound you hear is your comfortable smugness being swallowed up by evidential quicksand.

You find — if you are willing to look — a real man in history, acknowledged by even his pagan detractors as someone worshiped by his followers as God and reported to have been raised from the dead. You find an enormous body of ancient literature, preserved with uncanny accuracy unmatched by any other ancient texts, written by eyewitnesses whose accounts depict extraordinary events, while displaying their first-person storytellers in a harsh light utterly inconsistent with mythical generation. You find an abundance of archaeological evidence confirming many of its story characters and otherwise-obscure ancient places and customs.

And you find an empty tomb with no good explanation save that proffered by those who then saw him in the flesh: that his His claims could not be ignored, and that we would no longer have the luxury of dismissing Him and His followers as just another “belief without evidence.”

Of course, the Goddess is free to believe as she chooses, as we all are. But to dismiss such evidence out of hand, and posit in its stead a world where we can by denying it “start living rationally,” is, well, irrational, and does not demonstrate true intellectual integrity.

A common shorthand used by physicians when documenting a physical exam finding or lab result is “WNL”, meaning “Within normal limits.” We had a standing joke in my medical residency for those would document things they had never actually examined — “WNL” meant “We never looked.” And it likewise describes perfectly our modern skeptics who dismiss all religion as foolish, irrational fantasy. Some of it surely is — but being half-right means you’re all wrong. There is a price to pay for examining the evidence for Christ and the claims of Christianity, a price many are unwilling to pay: if you tackle this pursuit honestly and objectively, it will likely cost you your life.

But then, someone famous once said, “He who loses his life for My sake, will gain it.”

In my experience, it’s the best deal I’ve ever gotten. And that’s my advice to Amy.

On Miracles: Jesus of the Pagans

Third part of an ongoing series on the problem of miracles, and evidence for the Resurrection:

It has been said that Christianity is the only religion which traces its origins to the humiliation of its God. As followers of its crucified leader dispersed widely after its germinal events, traveling great distances from a remote corner of the Empire over dusty Roman roads, they indeed told a tale bizarre in every respect. How ludicrous the story of a God made man; who worked miracles among men; who suffered the most heinous execution the Romans could devise. A man who, if these fables be factual, arose from the dead, utterly transforming the lives of all who saw Him — these same men who audaciously claimed to be eyewitnesses to this mysterious manifestation.

It has been said that Christianity is the only religion which traces its origins to the humiliation of its God. As followers of its crucified leader dispersed widely after its germinal events, traveling great distances from a remote corner of the Empire over dusty Roman roads, they indeed told a tale bizarre in every respect. How ludicrous the story of a God made man; who worked miracles among men; who suffered the most heinous execution the Romans could devise. A man who, if these fables be factual, arose from the dead, utterly transforming the lives of all who saw Him — these same men who audaciously claimed to be eyewitnesses to this mysterious manifestation.

The people of the ancient world were no strangers to quixotic stories, to endless tales of gods and goddesses, myths and magic. Rome in its pragmatic wisdom absorbed them all, with their blood rites and orgies, their asceticism and temple prostitutes. Such tolerance kept the Empire unified and the conquered content; no sense risking unrest and rebellion over senseless fantasies.

Such legends amused and titillated, and their rituals provided feeble comfort in a brutal world ruled by heartless Fate. Yet Christianity was not merely another imagined tale of jealous gods and devious deities, but carried in its implausible story a spark fully absent from pagan fables: the flicker of hope in hopeless darkness, of purpose in a world chained and weighted to emptiness and futility. This spark fell upon the dry straw of a desperate world, and started a conflagration which reshaped that world in ways unimaginable.

Continue reading “On Miracles: Jesus of the Pagans”